The morning of Sunday 30th April 2017 will stick in many peoples’ minds for a long time. As the mountaineering world woke up to the awful news that one of its brightest lights had perished while acclimatising on Nuptse, climbers and non-climbers alike took to social media to express their shock at the loss of one of the all-time greats. Disbelief gave way to universal appreciation for the man and the mountaineer, with many personal messages and anecdotes showing how many people had been inspired by his achievements.

And it wasn’t just in the mountaineering community that the shockwaves were felt; the story penetrated the wider consciousness by making national TV news in many countries, this particular mountaineer as headline-worthy in death as he had been in life. As pictures came in of his body being removed from the mountain, still it was almost impossible to believe that the man many believed to be the greatest alpinist of his generation – Ueli Steck – was gone, aged just 40.

Trek & Mountain interviewed Ueli in early 2014, several months after his sensational solo climb on the south face of Annapurna, and later the same year at Kendal Mountain Festival where he gave a brilliant – and funny – talk to an enraptured audience. In this article, we will revisit themes discussed in those interviews, and attempt to condense his extraordinary achievements into a few thousand words, using quotes from Ueli himself and his peers. But to begin, we trace Ueli’s path from a climbing-mad teenager to becoming one of the all-time greats of mountaineering…

Early days and the Eiger

Born on October 4, 1976 in the idyllic Emmental valley near Interlaken, Ueli’s first sport was ice hockey, but at the age of 12 he went on a climbing trip with a friend of his father’s, Fritz Morgenthaler, to a mountain in the region called Schrattenfluh (2,092m). “Fritz was old-school,” Steck told Outside Online in 2012. “He threw me on lead right away. I thought it was normal to climb 20m with just two pitons and instructions not to fall.”

This experience was to change the direction of Ueli’s life, as he now devoted all his spare time to climbing. He quickly gained a reputation for climbing very fast and without fear, and was given a place on the junior national climbing team. But he soon became bored of competitions and indoor climbing, more interested instead in exploring the alpine wonderland in his backyard, and at the age of 17 he climbed a local testpiece, the east pillar of the Scheideggwetterhorn with his friend Markus Iff. They then turned their attention to the peak that had fascinated Steck since childhood, its famous north wall visible in the distance from the family home – the Eiger.

Already showing the signs of the meticulous planning and intensive training that would come to epitomise his approach a few years later, Steck trained for months before his and Iff’s attempt on the Heckmair route, and shortly after his 18th birthday the pair succeeded in climbing it in two days. Steck’s name would eventually become synonymous with the north face of the Eiger, and during his career he would climb nearly every existing route on the Nordwand, claim several first ascents, and hold records for the total number of ascents (43) and the fastest ascent (2 hours, 23 minutes).

If Ueli and his friends were rich in enthusiasm, they weren’t in cash, and like many aspiring climbers before and after, made do with what kit they could get hold of. “I bought some straight-shafted ice tools off some friends for very little money and I was climbing with these for three years,” he told us in 2014. “There were already other ice tools on the market, but I couldn’t afford them, and we were buying shoes in Italy because they were really cheap there.”

During the next few years, Ueli began ticking off alpine classics in the style he would become known for – solo and at speed. He soloed the Haston Couloir on the Mönch in 1998 and the Walker Spur on the Grandes Jorasses in 2001. He also made his first foray to the Himalayas in 2001 with an ascent of a new route on the west face of Pumori, while making his first significant mark on the Eiger north face with his and Stephan Siegrist’s new route, ‘The Young Spider’ in the same year. A sign of things to come, Ueli and his partner hit the headlines by climbing the north faces of the Eiger, Mönch and the Jungfrau in less than 25 hours, and the stage was now set for what would make Steck’s name known beyond the mountaineering world – the Eiger

speed record.

Peter Habeler and Reinhold Messner had made the first modern ‘speed ascent’ of the Eiger north face in 1969, completing it in 10 hours (the first ascent in 1938 took three days), however three decades later the record stood at 4 hours 40 minutes, as posted by Italian Christoph Hainz in 2003. Steck’s times on the north face had been getting progressively faster, and in 2007 he destroyed Hainz’s time by 46 minutes, using a rope to belay himself on only three, short sections.

However incredible his feat of climbing the mile-and-a-half high face in less than four hours seemed, Steck discovered soon after that he had the potential to do it even faster – much faster. This realisation came about when he visited the SFISM (Swiss Federal Institute of Sports Magglingen) and was told that, although fit for a mountaineer, he was nowhere near the level of the best athletes from other sports. For Steck, this was a turning point as he realised that by adopting the methods and training in use elsewhere, he could become capable of a far higher level of performance in the mountains.

During the ensuing year, Ueli worked with a dietitian, mental coach and fitness trainer during a training programme that was more advanced and challenging than any seen before in mountaineering. On February 13th, almost one year to the day since he first grabbed the record, Steck posted a time of 2 hours and 47 minutes to break his own record by an astonishing 25 minutes. The harsh training regime and meticulous preparation had paid off – with interest – and the die was cast for the rest of the Swiss’ alpinist’s career.

The Eiger record was just the start of a momentous 2008 for Steck. He would go on to set a mindblowing time of 2 hours 21 minutes on the Colton-Macintyre route on the Grandes Jorasses, he put up the hardest rock route to date on the north face of the Eiger, ‘Paciencia’ (F8a, 900m), and he and partner Simon Anthamatten won the 2009 Piolets d’Or for their route ‘Checkmate’ (VI, 85° ice, M7+, A0, 2,000m) on the north face of Tengkampoche (6,500m) in Nepal.

Many more Himalayan adventures were to come, but Steck always returned to ‘his’ peak, taking the record back from compatriot Dani Arnold in 2015 with a time of just under 2 hours 23 minutes (during which he was ascending at a rate of 695m per hour). Steck said: “It’s a bit like my laboratory, this territory that I know so well that I’m confident to explore my limits. I will never be done with the Eiger!”

Ueli in his ‘laboratory – the Eiger north face IMAGE: Jon Griffith

Speed climbing in the Himalayas

Climbing fast in the Alps is one thing, but doing the same in the Himalayas with as little as a third of the oxygen available to the body on its highest peaks is something completely different – but, as ever, Ueli was more than up for the challenge. He did not underestimate the difficulties he would face, however, as friend and photographer Robert Bosch recalls: “In the Himalayas, he didn’t set out intending to start by tackling the hardest 8,000s. He took things a bit at a time, progressively getting used to the terrain and developing his own methods. That’s what puts a being in a class of their own in the world of high mountains.”

He’d already climbed the likes of Jannu, Pumori, Tawoche and Cholatse by 2007, but Annapurna would become another peak synonymous with his name in time, and not always for positive reasons. His interest in the mighty south face – one of the hardest and most dangerous faces in the Himalayas – was piqued by legendary French climber Jean-Christophe Lafaille, who had had one of the most epic ‘epics’ of all time while climbing there in 1992. “It was when I read Lafaille’s story that I started to dream of going there and completing that ascent,” Ueli said, talking about the unfinished Béghin-Lafaille route. In one of the greatest survival stories ever, Lafaille had retreated alone down the face for five days after his partner Pierre Béghin had perished, down-climbing and rapelling with a broken arm.

Steck intended to complete the Béghin-Lafaille route alone in 2007, but was hit by rockfall and was lucky to be alive after falling 300m down the mountain. The next year he returned with Simon Anthamatten, yet he selflessly sacrificed his summit attempt in order to mount a rescue of Spanish mountaineer Iñaki Ochoa de Olza who was stranded and in desperate trouble on the East Ridge. Unbelievably, Steck and Anthamatten’s ‘training route’ for Annapurna that year, a beautiful new line on the north face of Tengkampoche, was good enough to win the pair a Piolet d’Or in 2009.

After the previous two years’ events, Steck decided to give Annapurna a rest for a while, concentrating instead on more speed projects in the Alps (Matterhorn north face solo in 1 hour 56 minutes, north face of the Droites via the ‘Ginat’ solo in 2 hours, 8 minutes), in Yosemite, and elsewhere in the Himalayas (south face of Shishapangma solo in 10 hours, 30 minutes, Cholatse, Cho Oyu and Everest without oxygen). However, after the infamous confrontation between Simone Moro, Jon Griffith and Steck with Sherpas on Everest in 2013, Ueli returned to Annapurna to take care of unfinished business. This time the result was spectacular: a solo ascent of the south face in just 20 hours (round trip of 28 hours), that set the mountaineering world on fire. Photographer Dan Patitucci said: “I could see he was in a different mental place, more serious, focused to begin something so severe there are only a few on the planet who could even contemplate such a thing – to solo an 8,000m peak via a new line, with only a small pack, and without oxygen.”

What should have been Steck’s career-defining moment, however, was marred by a minority questioning the legitimacy of the ascent, citing Steck’s lack of proof (he had dropped his camera during the ascent) as a reason to doubt his story. Although the majority of his peers were in no doubt that Steck had done what he said he had, and he received another Piolet d’Or for the climb, a shadow was cast on his achievement, and it seemed that even in his moment of triumph Annapurna was proving problematic for Steck. Ueli said about Annapurna: “So many things have happened there. In 2007, the first time, I fell 300m. The second time, in 2008, we had to abandon with Simon Anthamatten to try and save the Spanish mountaineer Iñaki Ochoa, who died in my arms of a cerebral edema at more than 7,000m. And the third time, I literally risked my life; I took the risk-taking too far. And there was all that controversy over reaching the summit which will never end.”

But despite the negative associations he had with Annapurna, the exhilaration of the climb had undoubtedly left Ueli with an appetite for more high altitude adventures: “My inner fire is burning once again,” he told planetmountain.com afterwards. “It was almost extinguished after Everest (the ‘brawl’ – Ed). Now it’s flared up again, fully. This makes me happy and I think I’m beginning to find the fun in life once again!”

Everest, like for so many others, held a special fascination for Ueli, and despite being badly affected by his experience in 2013, he could not resist going back to to try and complete what he and Simone Moro had started. “I’ve gone back three times since ‘the affair’. I’ve had a lot of discussions with the Sherpas, thought about it a lot and learned. Everest is still a dream and I’ll never let go of the dream.” But first he had to recover from Annapurna, a feat that – despite even his amazing strength and resilience – took more out of him than anyone could imagine: “I have to be honest, Annapurna really screwed me in the end,” he told us. “I was done for a long time, mentally and also in my body. I was finished for more than half a year. I could not train at all. I was just done. So it took a while to get over and get back.”

Mentally and physically drained by the Annapurna south face ascent, 2014 was a quiet one for Ueli, and while 2015 saw him retake his Eiger speed record and climb all 82 4,000m summits of the Alps in 62 days, these were challenges that lay within his comfort zone, in which he was not pushing his capabilities to their limits in the way that he craved. But Ueli seemed to be getting the taste for fast climbing in the Himalayas back by 2016 while climbing on Shishapangma with David Göttler, and this set the scene for embarking on one of his most intense training periods yet for his return to Nepal to attempt the Everest-Lhotse traverse. According to his press team: “For the 2017 project, the Everest-Lhotse traverse via the South Col, Ueli trained hard for months on end. He counts more than 1,200 hours of training in the last year. This includes more than 80,000m of vertical gain, 848km running, and 296 hours of specific strength training for his arms and legs.”

In February this year, Ueli took off for the Khumbu Valley to start acclimatising. In just 13 days, he ran 236km at or above 4,700m elevation – two weeks where he literally gulped down more than 16,200m of vertical gain. “I need to know that my body is strong, otherwise I’m uneasy,” Steck admitted to Le Magazine L’Equipe at the beginning of April before leaving for Everest. Asked why he wanted to go back to Nepal, Steck replied: “The answer is simple; I get to stay longer in the mountains. I get to spend more time with myself, Tenji Sherpa and the Himalaya. And now I’ll just go; and only worry about the events that lie ahead of me. Day by day, one by one. It is the here and now that counts. What comes next is uncertain in any case.”

Dedicated to training

One of the major influences that Ueli is considered to have had on mountaineering is his Olympic-level of training and fitness, with his preparation, training and diet on a par with the best in other sports. He is not the only alpinist to have taken training to another level, but he perhaps embodied this new era of professionalism more than anyone else. He had always trained hard and prepared meticulously, but it was after his first Eiger speed record and visiting SFISM that he took his training regime to a whole new level. For the past decade, Steck employed Simon Trachsel (also a coach for a professional cross-country ski team) as his physical trainer, and developed a meticulous programme combining trail running, strength training, backcountry skiing, mountaineering, and rock climbing.

Before Ueli’s last trip to Nepal, Simon explained what training they had been doing: “This is a training programme that we specifically developed for Ueli. It involves a very high workload of endurance training at different levels of intensity. However, in recent months, we also increased the amount of specific strength training.”

Although undeniably blessed with talent for his chosen vocation, several of his peers are convinced that it was Ueli’s relentless and scientific approach to training – combined with an holistic approach that went beyond training – that enabled him to rise to such heights. American alpinist Steve House, author of ‘Training for the New Alpinism’, in his tribute, said: “People say that Ueli was gifted, that his ability was innate, given. That’s completely wrong. Achieving an Ueli-Steck-level of mastery in climbing is a long-term commitment that requires a consistency that very few people are capable of. What made him that way is, in itself, worth studying, learning from. Here is what I believe people don’t understand about Ueli, and often

their own dreams. Ueli took the critical step of understanding the connection between his vision for climbing big mountains and what he did with his life every single day. Consistently. For a long time. Those cumulative daily actions were what made him the visionary that he was, and in our last email correspondence, a mere six weeks ago, he wrote: ‘I think we are still very far away from the perfect alpinist.’”

This thought is backed up by another climber who hung out with Ueli in his younger days, Will Gadd, who said on his blog: “Back when he was 19, I could see his ambition and drive, but he wasn’t that fast on the approaches, and there were a lot of climbers who were better technically than him. That is the truth. His athletic performances today puts him in the ‘He’s a machine, therefore I can never be like him’ category to most. Actually, the truth is bigger and far more important in its lesson to our own lives: he made himself into the machine. He busted his ass harder than anyone I know. Yes, genetics played a part for altitude, but his genetics were to be a cherub or perhaps hockey player like his brothers, not a ripped machine screaming into the ozone.”

This incredible dedication to becoming a better alpinist impressed all who came into contact with Ueli, not just other alpinists but the best rock climbers of the day too. Alex Honnold, speaking to Outside magazine, said: “He was the first to bring Olympic-style training to the sport. I think the thing that I took away from spending time with him was his dedication to training. Climbing is a lifestyle, but he was one of the first to systematically take the sport to another level. He was at such a high level and so disciplined. We’d go climbing together, and he’d be climbing as hard as we were, but then he’d go for a really long trail run. The climbing was just one tiny piece of his day.”

So what exactly did Steck’s training consist of, and which sports did he do? Well in numerous interviews he’s stressed his love for, and the importance of, running, and of course being Steck, this meant running uphill in his local mountains for 1,000m of vertical ascent or more. He also did plenty of strength work with weights in the gym, and lots of rock climbing – however, the exact training programme depended on his next project or goal – a speed record on the Eiger is very different to a big Himalayan expedition, for example.

When we spoke to him in early 2014 he said: “Like every athlete, there is no average day – your work depends on your project and it moves on. It’s a lot of running, weight lifting, climbing; it’s so many things together and it changes as you have to work in periods, not a particular day. If you look at other training schedules, it’s like this. I do a lot of six-week periods then it changes, it’s not 365 days a year. There is also a lot of planning. Then you have to adapt as something may go differently to what you expect. You need a lot of flexibility as well.”

In an interview with DaddyGoneClimbing.com, Ueli listed the four keys to his training as being uphill running, core strength training, weight training and climbing. For his original Eiger speed record, his weekly training plan went like this:

MONDAY: 1 hour running–Intensity 2 / 1 hour stretching / 1 hour stabilization (core) training / slideshow.

TUESDAY: 2 hours running–Intensity 2 / 1 hour stretching / 1 hour mental training / slideshow.

WEDNESDAY:

4 hours climbing in the gym / 2 hours running–Intensity 1 / 1/2 hour stretching / slideshow.

THURSDAY:

4 hours climbing in the gym / 1 hour stretching / 1 hour mental training / slideshow.

FRIDAY:

1.5 hours running–Intensity 1 / 1 hour stretching / 1 hour mental training / slideshow.

SATURDAY:

3.5 hours running–Intensity 4 / 1 hour stretching / slideshow

SUNDAY (REST DAY):

Climbing with my wife 4 hours / 1 hour stretching

Before Ueli’s solo ascent of Annapurna’s south face, he had been running up peaks with as much as 1,700m of ascent, such as Niesen (2,362m), which he did up to three times a day. And for the Everest-Lhoste traverse, Ueli introduced weight-training for six weeks, a new element to his programme: “I lacked power and so I had to add some intense work to enable me to improve my performance. The next six weeks will be devoted to a lot of mountain running, with or without crampons depending on the conditions, the duration and the distance. In the end, I’ll only be doing very short runs, what’s called interval training.”

Ueli ideally liked to run four or five times a week, during sessions which he measured in height differential and not in kilometres. “One session of a dozen kilometres is about 1,700m of height differential. It’s short, but intense, and suits my sport. I know I have more in me and trail running can help me improve. On my record Eiger climb, my average pulse rate was 156 for a rate of climb of 700m gross ascent per hour. I think the limit is 800 to 850 or a bit more”.

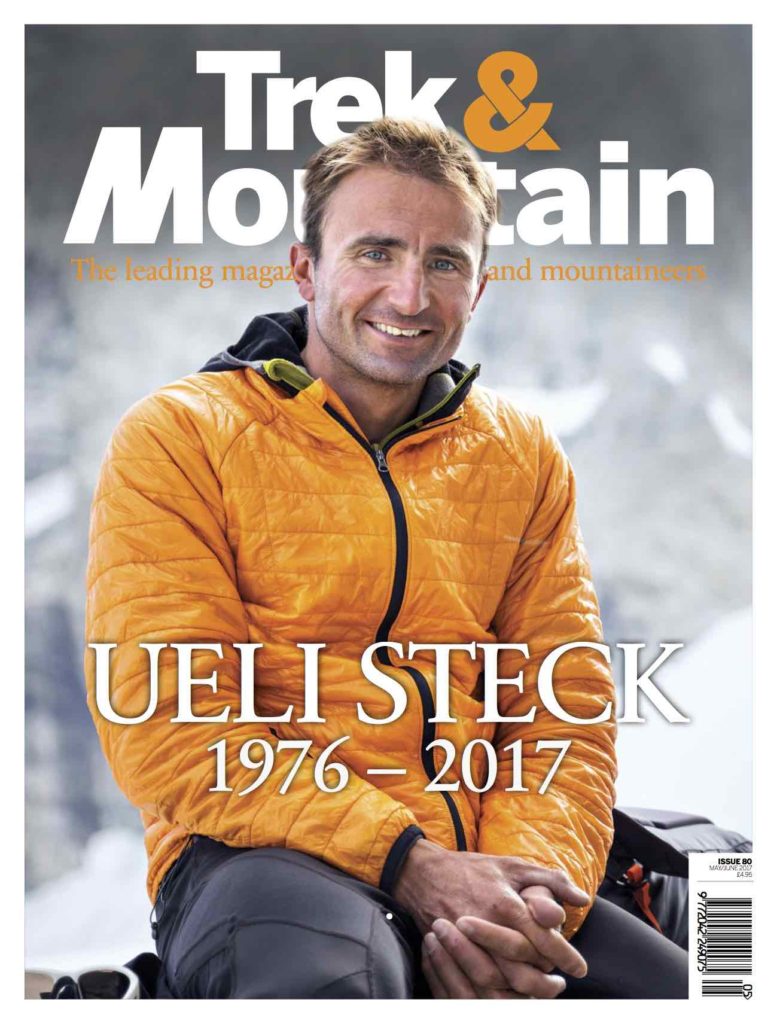

Just how much more Ueli had in him we will now never know, but those close to him say he was in the best condition of his life for his last expedition. Photographer Dan Patitucci, who took our cover image and was a training partner of Ueli’s, spoke to Outside magazine about Ueli’s condition once his training for the Everest-Lhotse traverse was completed: “Before Ueli left, I’d never seen him so happy. He was by far in the best shape I’ve ever seen him. The guy was never not fit, but this was a whole new level. He was so comfortable in his own skin and had just recognised how hard he’d been working. A message came through a few days ago that he’d run from base camp to Camp II in 4.5 hours. It’d take most people days to do that.”

Giving a talk at Kendal Mountain Festival, Ueli was warm and witty personality IMAGE: Amanda Lu/KMF

For the love of it

Despite all the success, sponsorship and social media followers, Ueli did everything for the love of it, whether running, rock climbing, ice climbing or speeding up north faces – and that is clear to anyone who has ever met him. Even when training hard he had time to appreciate the beauty of the mountains, as he told T&M in 2014: “Every moment has this beauty, this speciality. Sometimes it’s just simple; like two days ago I was on my own… I have a hill close by where I run a lot. I’ve run there a thousand times already, at least. And the day before yesterday I was up there and then, looking into the mountains, it was such great light and you could see there was fresh snow and it’s kind of like, ‘oh, it’s so cool’. I think that these days a lot of people miss that. Everybody now seems to be preoccupied with their phone and Facebook; it seems that the most important part is that as soon as they get back they have to post where they were, what they did and they just miss the moment. I don’t bring a phone to go for a run; I just go for a run and just enjoy it. I don’t run with music; I like to listen to the natural sounds.”

Although he was perhaps one of the first stars of social media and benefited from a huge following on Facebook, Steck actually despised the act of glorifying one’s mountain accomplishments and emphasising the hardship or dangers of the endeavors. “The worst change I think is GoPro cameras,” he told us in 2014. “I think everything is filmed and I think people are just missing the point of climbing. You see all these people walking around with these GoPro cameras – it looks so stupid! For me that’s really, really important. You know, like, soloing something it means you’re alone; there’s nobody on the face to film. And there is a lot of things, like, if you do a climb and you can bring a camera team with you, then it’s not a hard climb. That’s just how it is. And sometimes people forget that, but because there is footage people think ‘whoa’. But that’s not my world.”

Will Gadd echoed these sentiments in his tribute to Ueli: “In an age where athletes define their own ‘accomplishments’ on Instagram and spray endlessly about their self-imposed ‘hardship and suffering’, you didn’t. You climbed, and loved it, and thought long and deeply about the mountain game. The suffering wasn’t because it was smaller than the goal. To realise great dreams you need great goals. You lived your dreams better than anyone I’ve ever known.”

Ueli was very philosophical about his achievements too, and played down the significance of records and ticking off hard routes – surprising to some, since his reputation had been made on such things: “I think it’s very important to realise why you are doing it –and in the end it’s just for your personal experience, nothing else. I think this is very important, that you should just do stuff that you love to do and that’s about all. It doesn’t matter how hard you climb or how fast you run; what matters is just doing it. If you like to do it, do it – all the rest is secondary. It doesn’t change anything if you climb the Eiger in two and a half hours or not. The world turns the same way round the next day; you know, it doesn’t change the world.”

Although Ueli loved people, he also enjoyed being in the mountains on his own: “I think that it’s very special when you are alone in the mountains. That’s why I love it so much. It’s completely different; you’re much more aware of what’s around you, and there’s nobody disturbing you. And you’re not talking with anybody; it’s just you and the mountain and it’s much more intense. I think if you’re somewhere alone, you see everything, but if there’s two of you and you are talking or whatever, it’s different. But then on really hard climbs you really focus on the climbing so you don’t see the landscapes of course, but that’s a different experience. Then, maybe you see just this little part of the face, but you see everything equally. You don’t see the whole mountain – just this part which is also great.”

The man

The wave of shock and emotion that followed the news of Ueli’s death on April 30th is unprecedented for a climber or mountaineer. But what caused such a response, an almost universal empathy for a man that many people had never even met? I think there are several reasons for this. Steck was one of the few people that captured the attention of an audience beyond the mountaineering and outdoors community, his Eiger speed climbs in particular catapulting him into the wider consciousness. In death he became headline news once again, with a new audience becoming aware of a man touted by his peers as one of mountaineering’s all-time greats. Steck’s natural humility and kindness also endeared him to the many people he met or followed him on social media – so much so that many people felt like they had lost a friend when news of his death circulated. And finally, he was an inspiration to so many, be it his peers or the thousands of hikers and climbers who were motivated by Ueli’s incredible exploits to go further or faster during their own, more modest, mountain adventures.

His friends talk about a man who, despite the fame, never changed underneath, and was as warm, humble and down-to-earth as he appeared to the wider public. Steve House: “I feel lucky to have known Ueli. And the world is better because he lived the way he did. His spark of life was so bright. His vision was so far reaching. In recent years, I found his humility endearing. He was vulnerable with people, something that requires a rare strength and sensitivity. We need people like him, human heroes. We need to be inspired by greatness. We need Ueli to help us deal with our own puny fears. We need him to show us what it really means to live by

one’s dreams.”

And photographer Jon Griffiths, who Ueli spent a lot of time with over the last few years, said this in his tribute: “He was the perfect example of humility and honesty in an ever ego-centric online world, and he really cared for those in his inner circle. Ueli had a sensitive and loving side to him that made him a true friend. He would drop anything to help you out, no matter what; a rare quality for a person who could easily have let his climbing status define who he was. Ueli never changed who he was deep inside, a carpenter from Emmental. A guy who used to hand out lift tickets and save up to pay for his climbing, a man who in the prime of his professional career would come and stay with me in Chamonix and be happy to sleep under the kitchen table as my flat was so small, and a man who was sensitive and kind.”

Stephen Venables mentions Ueli’s selflessness on the south face of Annapurna in 2008: “Amidst all the talk of Ueli Steck’s extraordinary achievements, there seems to be little mention of what, to me, was his greatest year – 2008. That spring season he and Simon Anthamattan climbed a beautiful new route on Tengkangpoche, before attempting the huge South Face of Annapurna. It was just hours after descending from their recce that Ueli and Simon set off again, this time for the East Ridge of Annapurna to try and rescue the sick Basque climber Iñaki Ochoa de Olze. Ueli didn’t manage to save Iñaki’s life, but – at the cost of huge effort and personal risk – he was there to offer comfort to the dying man.”

Many, many people have stories of meeting and chatting with Ueli, and we saw this first hand when we bumped into him at Lukla in 2016. Not only was Ueli happy to talk about his own plans, he was interested in where everyone else was going and what they were doing.

We talked to Tenji Sherpa, who despite being overwhelmed by grief for the loss of his friend and climbing partner, managed to send us some words about Ueli and what he meant to him. “He was my best climbing partner since we met in 2012 and we climbed Mount Everest together. Between 2012 and 2017, I climbed many mountains with him (Everest, Cholatse north face, Island peak, Eiger, Jungfrau, Mönch and many more, and we spent many times together, we share all things with each other. I would like to give thanks for those unforgettable moments we shared – you are the hero, you leave an amazing legacy for generations of climbers. Ueli had a sensitive and loving side to him that made him a true friend.”

Place in history

Where does Ueli Steck stand in importance in the history of alpinism? Despite it being near impossible to compare the leading characters from different eras of mountaineering history, it’s clear that his peers held him with the greatest respect and regarded him as a leading light of their generation. Steve House again: “Ueli shaped our community and he shaped the sport of climbing, I believe for the better, by first seeing, and then becoming what is humanly possible. Benevolent leadership by good example feels rare in today’s fractious world. It is something few people ever accomplish. Ueli lived and died as that kind of leader.”

And this from Jerry Gore: ”He was the greatest alpinist of his generation. He was a true visionary. He was the inspirational climbing machine, and he will continue to inspire this and future generations of mountaineers.”

What about the old guard, who themselves have climbed with the greats from the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s? Sir Chris Bonington described Ueli in a BBC interview as “one of the great mountaineers of all time”. And Reinhold Messner, in an interview with Swiss newspaper NZZ said: “Ueli Steck was someone who made things possible that were not possible before. In my day, ten hours was a fast ascent of the Eiger north face. Two hours and 23 minutes [Steck’s current speed record for the climb] was absolutely unfathomable at the time.”

However, Messner – ever forthright in his views – also touched on a subject that has drawn criticism of Steck from a few over the years: that of his preference for speed ascents over first ascents: “Steck always had bold aspirations and was constantly evolving, for which I admired him. However, I was never that taken by his speed-climbing pursuits. To me, it’s just not that important whether someone climbs the Eigerwand in 10 hours or in three. I was much more impressed, for instance, that Steck managed to climb all 82 4,000m summits in the Alps in a single summer.

Many would consider this crititism unfair, for he certainly did put up new routes – and significant ones too – including ‘Paciencia’ on the Eiger, ‘Blood From The Stone’ on Mt Dickey in Alaska, ‘Checkmate’ on the North Face of Tengkampoche, and of course the completion of the line on the south face of Annapurna that Lafaille and Beghin had attempted in 1992. And in an age where the feast of unclimbed peaks, faces and lines available to previous generations just don’t exist, Ueli’s focus on an ‘exploration of athleticism’ rather than a geographic exploration (as the Piolets d’Or put it recently) is perfectly understandable.

Indeed Ueli made no apology for this, as he told us in 2014: “I’m not interested just to climb a mountain because it’s never been climbed. For me it really needs to be a challenge, like a performance for myself, otherwise I’m not interested in it. It really has to have something about it, especially climbs that people have tried before and they were not successful. It makes it much more interesting because you know, ‘ah, that’s hard’.”

Despite a small minority questioning some of his achievements – and in particular the Annapurna south face solo – the people who actually climbed with him have no doubts. Steve House: “When a major figure of climbing like Ueli dies, there is always second-guessing and criticism. In my opinion, Ueli came in for more than his fair share of criticism. Most of the criticism, I believe, is rooted in human insecurity. People didn’t believe anyone could do what he did, their own personal fears too overpowering to even allow the possibility of his excellence, of his achievement.”

Although Ueli would say that the doubters didn’t bother him, Jon Griffith alludes to the pressures he may have felt in his touching tribute: “In the end (he) couldn’t stop himself from being pressured from the last few years of critique and baseless accusations from people who refused to believe what was possible, simply because they had never seen him move and climb like I have done. The Everest-Lhotse traverse would have been his redeeming climb in the eyes of the world; proof of his abilities that should never have been needed.”

However he is remembered – for his speed climbs, the Annapurna south face solo, the training and professionalism, the kind and humble man… Ueli Steck’s name will forever be etched in the annals of mountaineering history. Farewell, Ueli… and Godspeed.

Words: Chris Kempster Images: Jon Griffith, Amanda Lu, Tenji Sherpa, Dan Patitucci