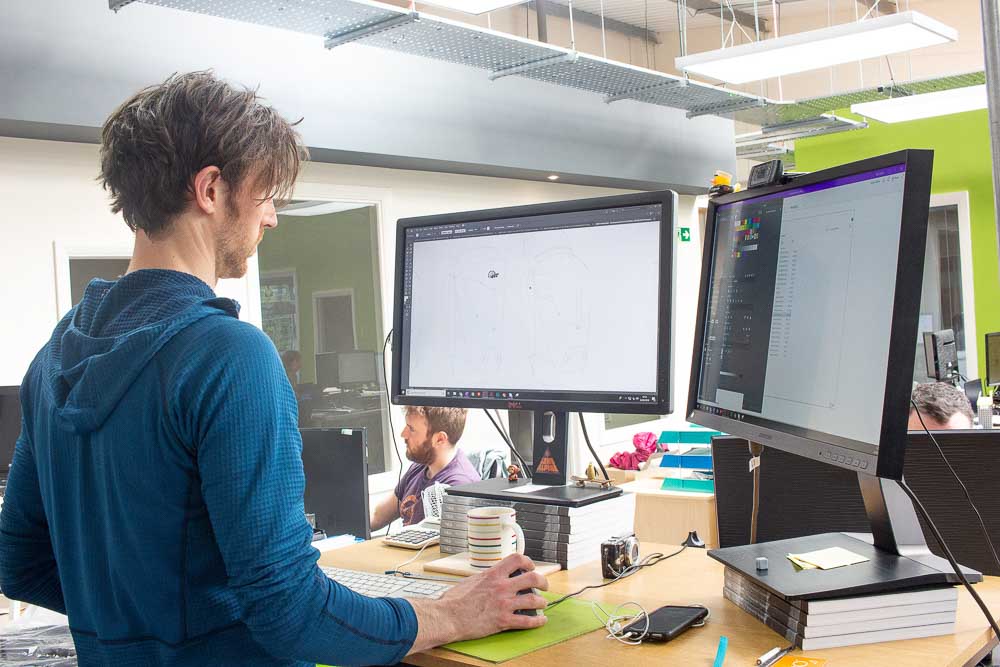

In a subtly different world, Lowe Alpine pack designer Dan Jenkin would be elbow deep in toasters, kettles and other sundry domestic appliances. After graduating with a degree in product design from Sheffield Hallam and with a year of hands-on experience under his belt, he had the choice of a full-time post with Morphy Richards or six months working for pack design specialist Tim Fish.

It was a crossroads, he says, but it’s not really much of a surprise which turning he took. There’s a clue in the lanky frame, dishevelled, tousled hair and battered fleece – Dan, 29, has been a climber for pretty much as long as he can remember. It’s the reason he chose to move from his native Bristol to study on the edge of the Peak District and it’s the reason that he chose a precarious six-month contract with the UK’s top pack designer, rather than the assured security of a long term future in electric kettles. ‘It was a pretty easy decision really,’ he concedes.

Fast forward a few years and Dan’s one of Lowe Alpine’s lead pack designers. He moved to the brand along with his pack-ninja boss, Tim Fish, and he’s one of the main designers behind the new Altus, all-mountain pack range with more ranges to come shortly.

What drives him? ‘Seeing the pack in store’, he says. ‘Or realising someone’s actually carrying the pack you designed as they walk past you out on the hill’.

Dan says his favourite parts of the design process are the beginning and the end. He kind of lights up at the thought of the endless possibilities that come with the initial concept, when it’s a question of unpicking the puzzle of what a pack needs to do and how to make sure it does it. And, at the other extreme, the end result.

The process between those two points can be difficult – ‘Some days are harder than others,’ he says. ‘But there’s always the fascination with finding solutions to different problems.’

What sort of problems? Well, a typical one would be the carry system of the new Halcyon mountaineering packs that we previewed at the recent ISPO show. It needed to be decently light, flexible enough not to impeded movement or feel rigid and restrictive, but still be able to handle the heavy climbing hardware that mountaineers need to haul.

The end result is a carefully contoured mix of sprung metal frame and dense foam padding (see images) that you can tell Dan’s quietly proud of. You and I will have to wait until this autumn to see how it works, but he – of course – has tried it already. One of the perks of designing it in the first place.

His first pack? A small, non-technical Karrimor day-sack, but still a satisfying moment seeing one being used in the real world for the first time. And the one he’s most proud of? You’ll have to wait and see. It’s due out next spring, is ‘technical’ and its proud dad says it will first see the light of day at next month’s OutDoor by ISPO trade show in Munich. Watch this space.

Last but not least, how does being a climber himself make for better designs? It’s not just that he has an instinctive grasp of what climbers need, he says. More generally, as an end user, he gets how small details matter to specialists doing activities he doesn’t know well. It’s kind of a question of understanding what to ask rather than knowing the answer to begin with and it really helps. Toaster users? Not so much.

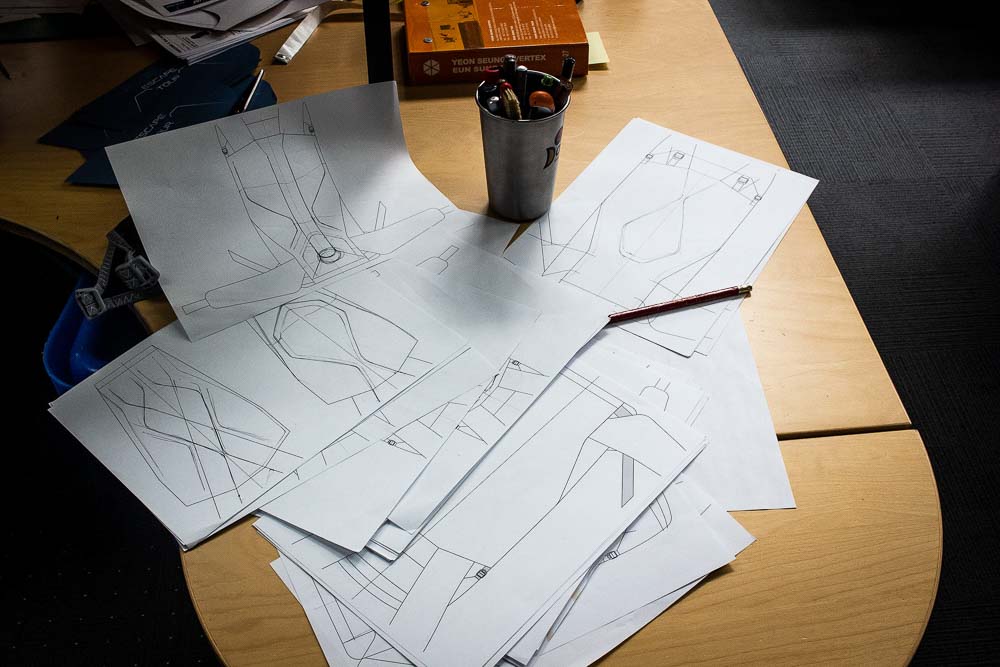

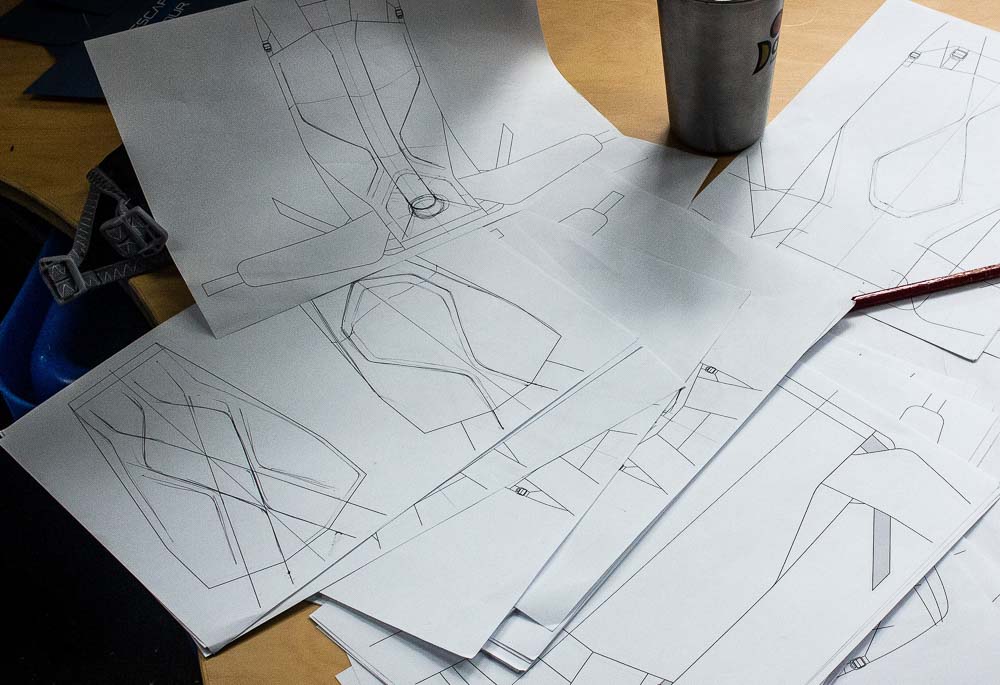

It all starts with a drawing

The Altus is born

The new Lowe Alpine Altus is one of the best all-season, all-mountain packs we’ve used, but how did it get that way? We asked Dan to talk us through the process from concept through to finished load-hauler.

It all starts with the current pack range and a look at where there are gaps and what could work better. Generally a Lowe Alpine pack will be on sale to customers for around four to five years before it’s replaced, with maybe a change of colour scheme after a couple of years.

If the pack is really outstanding, a new version might just mean tweaking the original design and style. However for something like the Altus, which filled a gap in the Lowe Alpine range, it means starting from scratch.

The first step is working out what the essential features are and what it needs to do. It’s a collaborative process with a lead designer and a developer pulling in ideas from the whole Lowe Alpine team. That means colleagues, sponsored climbers and experienced guides who all have ideas as to what’s needed and not. There’s input from Lowe Alpine teams in other countries that may influence design too. For example, German users like front and side-zip access in a way that UK walkers don’t, hence the pack gets them for continental happiness. The continentals also like brighter colours it seems, for Brits, greys and black are the most popular choices.

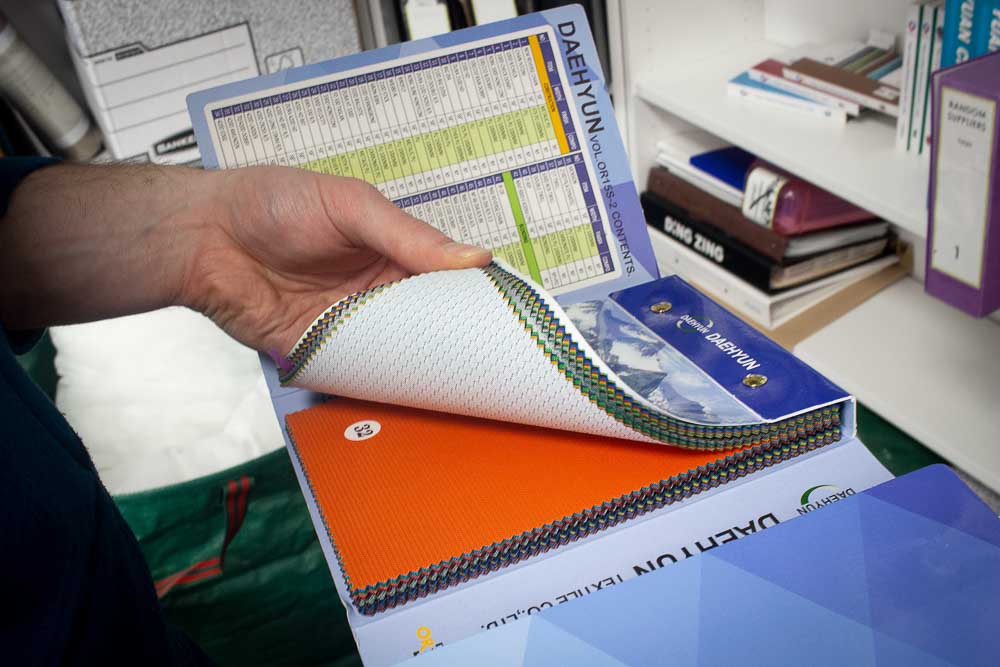

Price matters too. ‘You can’t produce an Arc’teryx-type pack at a Sports Direct price,’ says Dan. It’s about getting the balance right between a quality pack at a reasonable price and one that might use super high-spec components, but be priced out of reach as a result.

Other basics will include what capacities the various models need to be and, at a very early stage, whether and how many ND – women’s specific – packs there will be in the range.

Lowe’s ND packs are emphatically not just shrunk down, pink versions of the regular range marketed at women. Certain ranges, like the Altus, have had the ND packs crafted to suit the female form and the way women prefer to carry heavy loads, based on research conducted with the University of Cumbria.

Most crucially for the Altus, research showed that a woman’s lumbar and iliac crest (the bony bit at the front of your hips where you should place the top of the hip-belt) was greater than that of the average man. So on the Altus the lumbar curve has been reshaped so it is roughly an inch higher on the ND styles to better fit a woman’s anatomy.

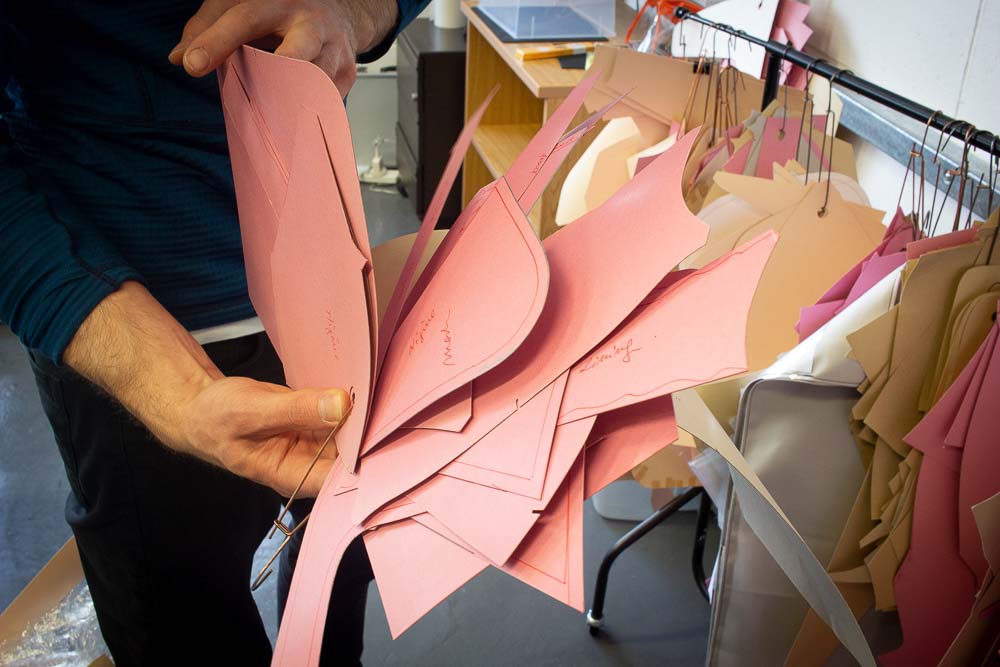

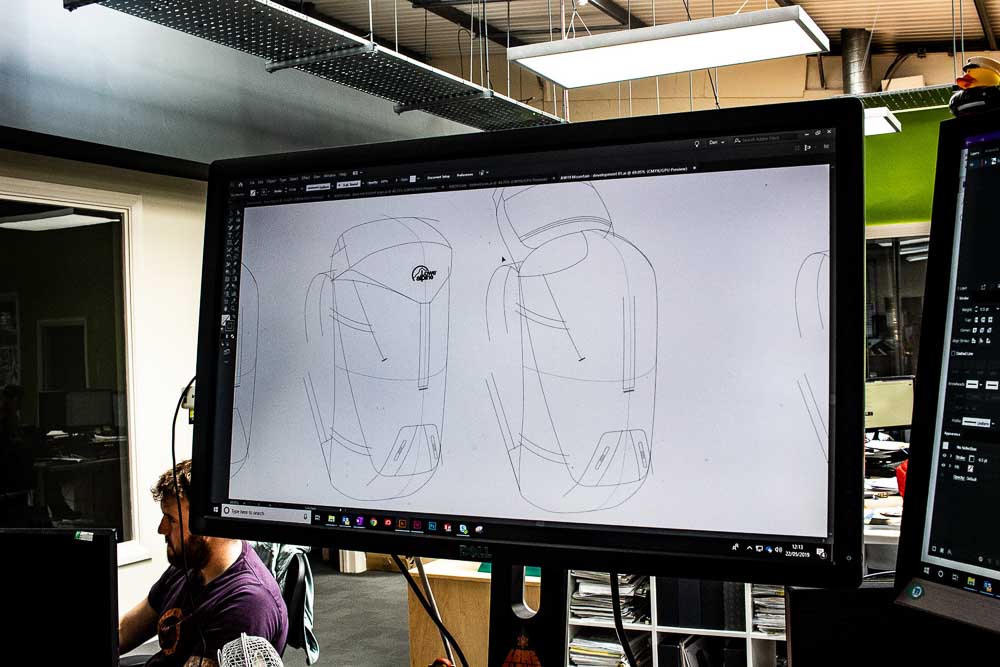

Once the basic designs have been drawn up, things get interesting. Lowe Alpine’s factory is in Vietnam, a hot-bed of pack manufacture, so there’s a process of too-ing and fro-ing of CAD files between the designer and the factory culminating in a first prototype. The bulk of the works happens in Vietnam, but the Alfreton offices also allow the team to work on prototypes here in the UK, with faster turn-around and more direct input.

It’s also where pack fabrics and components are lab-tested to make sure they’re fit for purpose – no point in a pack fabric that wears out the first time you drag it over a rock.

Once the first prototype samples come back, testing begins. The packs are used by the designers themselves, other members of the team and sponsored athletes and guides who’ll all feedback on what works and what doesn’t. It might be something as basic as the foam density of the lumbar pad, or just a quirk of a pocket that doesn’t quite work, but it’s all relayed back to the pack developers to improve.

Usually there will be four to six prototypes in each model in the new range, all of them used and reviewed before being tweaked. Some of that will happen in the UK, but about halfway through the development process, the designer will fly out to the factory in Vietnam for two weeks. The process there is the same as in the UK, reviewing and testing samples to work out what needs changing, but being at the factory means the whole process is accelerated. Working directly with the pattern makers and team in our sample room at the factory we can do about six weeks work in two’ says Alex.

Then, right at the end of the design process, some of the development team will head out to Vietnam again, this time to help with any production issues and review the ‘pilot run’. An early, smaller production run to check that everything is being made correctly and to spec before the pack goes into full production.

As far as the design itself goes, it’s not always about radical innovation. If something’s proven to work well already, why break it? So the Altus back system’s mix of a contoured dense foam padding with an internal alloy frame is far from revolutionary. But it’s been carefully refined so that it has just the right mix of support and flex so that it carries well without feeling stiff and restrictive.

It’s the really fundamental aspect of the pack that Lowe’s latched onto with its ‘World class carry systems for life on the move’ line.

It doesn’t mean the team doesn’t look at more radical solutions – check out the new Uprise packs where the back-system is covered with pack body fabric for example – and there’s a pooling of ideas and blue sky thinking during the design process. However the question is always whether there’s real benefit or if something is just innovation for innovation’s sake – because it ‘looks cool’.

The whole design / development cycle takes around six months and culminates in a run of what are called ‘salesman’s samples’, basically exact replicas of the final product in the correct sizes, fabrics and colours which are unveiled at an internal sales launch.

At this point, it’s just about job done. Barring the odd minor modification, the pack trundles off into production and is set free in the real world of hills and mountains. The pack team moves onto the next season and the next project.

And if a passing stranger seems to be taking an oddly disproportionate interest in your pack, hey, it might just be a proud designer basking in the satisfaction of a job well done.

More info: www.lowealpine.com