Do some basic research into waterproof outdoor fabrics and jackets and you’ll soon wander into swampy groves of statistics: Hydrostatic Head? MVTR? 40 Denier? What do they all mean and can they help you choose the right waterproof jacket?

How waterproof?

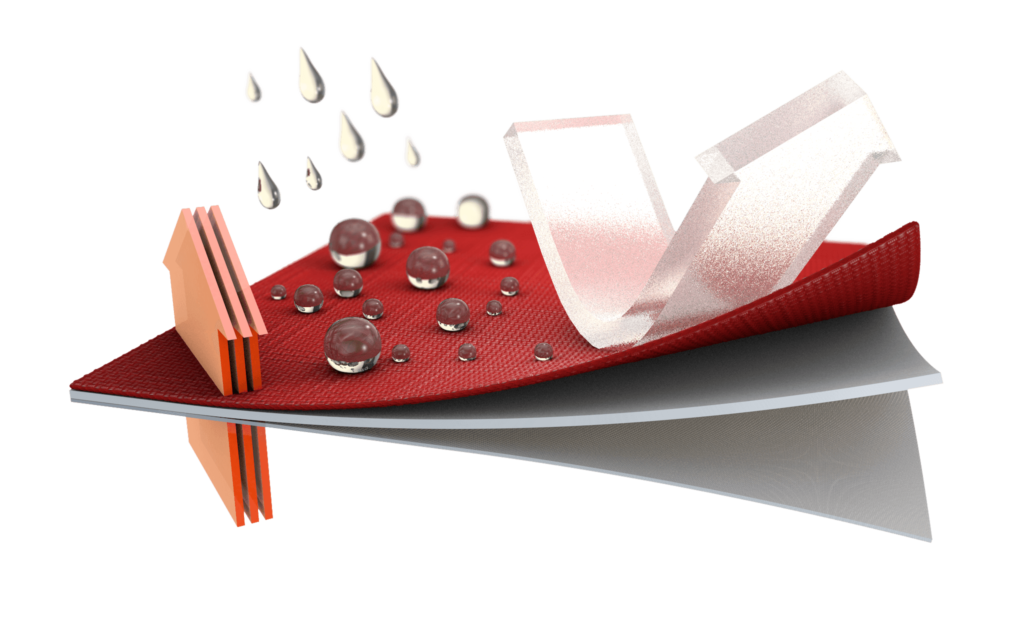

Hydrostatic Head (HH) is probably the easiest measure to understand and it’s a guide to the outright waterproofness of a fabric. If you thought waterproof was a binary ‘yes or no’ concept, go and stand in the corner, there are degrees of waterproofness. HH is measured in mm and is the height of a water column that the fabric will withstand before leaking. So if a fabric has a hydrostatic head value of, say, 20,000mm, it’ll cope with 20 metres of water. Obviously in the real world, the chance of finding yourself under a 20-metre column of water is thankfully pretty slim. What you may encounter though, is wind-driven rain and pressure from pack-straps or just leaning against, erm, a stream. Or maybe kneeling on a wet rock. The higher the HH figure, the more resistant the fabric will be.

So what are you looking for? Is higher better? Can something be ‘more waterproof’? The answer is ‘sort of’. Most fabrics from the likes of eVent, Gore-Tex and decent own-brand kit fall into a range of between 20,000mm and 30,000mm and that’s a good start-point for reliable, durable waterproofing.

The one top name fabric that falls short of this figure is Polartec’s NeoShell, which scores only 10,000mm in lab tests. Is that a problem? Well no and yes. By reducing outright waterproofness, Polartec has increased comfort and breathability – more about that in a minute – but at the same time reduced durable waterproofing. When new, NeoShell is fine and as waterproof – except in lab tests – as anything else, but as it ages and wears, the HH figure drops off. That’s not a big problem if you start off at 30,000mm, but NeoShell’s lower outright rating means with heavy use waterproofness can be compromised.

Last but not least, Paramo’s Nikwax Analogy system isn’t technically waterproof at all in the sense of resisting a column of water, but mostly functionally is unless you lean against a streaming wet rock or kneel in a stream, when localised pressure can force water through the fabric.

Our takeaway: Something around 20,000mm or more is a good start-point for a durably waterproof jacket, but if you’re prepared to compromise, you could trade some long-term water protection for better breathability and comfort.

Moisture Vapour Transfer Rate

Hydrostatic Head is at least a pretty straightforward measure, where things get really complicated is with another figure you’ll often see, namely MVTR or Moisture Vapour Transfer Rate. In simple terms, this is a lab test measure of how much water in vapour form in grammes will pass through a sample of the fabric over a 24 hour period, hence the ‘g/sqm/24hrs MVTR’. On paper it seems like a handy, objective measure of just how ‘breathable’ or ‘comfortable’ a waterproof fabric will be.

There are various ways of doing this, but none of them really replicate how a jacket performs on a human body, so while they’re a useful reference point, they’re certainly not definitive. When Polartec launched NeoShell, it argued pretty convincingly that different tests favoured different types of waterproof fabric and weren’t particularly useful. In real life, NeoShell is just about the most breathable waterproof fabric we’ve ever tried – watch out for the similar North Face Future Light technology appearing right now.

When Gore-Tex launched Gore-Tex Active a few years ago, they provided figures that showed the fabric was – in tests at least – more breathable in terms of MVTR than a cotton tee-shirt. How does that work? Presumably cotton traps the evaporating vapour rather than allowing it through, but does that make cotton less breathable than Gore-Tex? Hmmm… Thinner waterproof fabrics tends to score better here too. The fabric Berghaus uses for its Hyper 100 ultra-lightweight jacket, for example, has a claimed MVTR of 50,000 g/sqm/24hrs compared to 30,000 g/sqm/24hrs for the Alpkit Balance jacket we’ve just reviewed. Is it almost twice as breathable? It’s good, but not that much better.

Other factors also come into play, pockets create double thickness areas of fabric. Seam tape is non-breathable and reduces overall comfort and so on. Oh, and one last point, if the outer, face fabric wets out and is saturated with water, it doesn’t matter what the MVTR says, the fabric’s breathability will always be significantly reduced.

Our takeaway: Breathability, the rapid clearing of internal damp fug that goes with outdoor activity in a waterproof is harder to measure that you might think. By all means compare MVTR figures, but don’t get hung up on them, they’re just a very rough guide and there are so many different MVTR test standards that the numbers you’re looking at may have been produced by quite different test methods.

So What’s RET?

You don’t see RET values quoted as often as MVTR these days, but the theory is that they measure the same sort of thing. It stands for ‘Resistance of Evaporation of a Textile’ and counter-intuitively, the lower the number, the better the breathability – or the lower the resistance to vapour being evaporated through it. Got that? Anything from 0-6 is ‘extremely breathable’ or 6-13 is ‘good to very good’, 13-20 is ‘satisfactory’.

Our takeaway: More salt please. Again, if you do find RET values, treat them as a starting point rather than gospel truth.

Fabric denier

At last, a value that means something. In really basic terms, denier often expressed as ‘D’ as in 40D or 80D is a measurement of the thickness of the fibres used for a fabric. The lower the number the lighter and thinner the fabric in general. Most middle ground waterproof jackets will use fabric of around 40D with reinforced areas on, say, shoulders and fore-arms being 80D or so. A full-on, hard-core climbing jacket might use 80D fabric all round. Meanwhile a really lightweight fabric designed for use with down clothing could be as fine as 10D.

Occasionally brands will also quote weigh figures per square meter of fabric, Berghaus Hydroshell Elite Pro, for example is 47g/m2 while PHD’s ultralight 10X downproof material is just 26 g/m2. A standard weight waterproof jacket fabric is more likely to be around 100 g/m2. In general, the lighter the fabric the less durable it’s likely to be, but it is, in all honesty easier to look at the overall weight of the garment and whether it has heavier duty reinforcements.

Our takeaway: The denier of a fabric doesn’t tell you everything about it, but higher D numbers tend to mean a heavier, tougher fabric. Make sure you’re comparing apples with apples though. Nylon or Polyamide fabrics are tougher than Polyester. If you want tougher still, you’re looking at bespoke super fabrics incorporating the likes of Dyneema to up strength without adding weight.

Do stats matter?

In really simple terms, they’re a start point, but don’t tell the whole story. Is a cotton tee really less breathable than any waterproof jacket? And if a jacket is resistant to 20,000mm of water – a column of the stuff – is there any benefit to having a fabric that’s resistant to 30,000mm? So we’d say sure, look at the lab test figures, but don’t assume they tell the full story.