Will Harris talks to the Yosemite climbing legend and first man to free climb the Dawn Wall about pushing his limits and the important things in life…

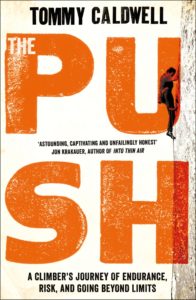

Tommy Caldwell has long been famous in climbing circles, known for his free climbing accomplishments on El Capitan, the 900m high granite monolith that dominates California’s Yosemite Valley. No one-trick pony, Caldwell has also pushed his climbing skills into the alpine environment, winning a Piolet D’or for his and Alex Honnold’s traverse of the Fitz Roy skyline in Patagonia. Until recently, outside of the climbing world, if his name was recognised at all it would have been for the high-profile kidnapping of him and his three climbing partners in Kyrgyzstan in 2000, a traumatic six-day ordeal that came to an end when Caldwell pushed their remaining captor from a ledge. That all changed with his 2014 free ascent of the incredibly difficult Dawn Wall on El Cap, a sporting feat which attracted mainstream media attention and attracted congratulations from Barack Obama, the US president at the time. We caught up with Caldwell to talk about all things climbing, his new-found renown beyond climbing and the process of writing his new autobiography.

First of all, thanks for taking the time to speak with us. You have been busy travelling to promote your new book; where are you now?

I’ve been on a plane almost every day for like a month, but I’m back home in Colorado for a bit. I’ve got a trip to the UK for a few days coming up. I climbed in World Cup competitions in the UK as a teenager, and got one day out on the grit; it was amazing, there was ice on the ground and it was super nice, and everyone was like ‘it’s never like this’. I don’t think that I’m going to get to climb on this trip as I’m pretty booked up, and I’ve been away from family a lot recently so I need to get home to them.

Going back to the beginning… how did you get into climbing?

My dad’s a mountain guide so I started with him when I was little – it’s what we did on every vacation during my childhood.

You had some early success in competition climbing? Would you have any advice for young climbers coming onto the comp scene?

Mild success I would say; I was always second tier. I thought I was going to win and then Chris Sharma came on the scene, and I would always come second. When I was that age, I was very angstful, which was motivating in a way. It’s what made me good, because I wanted to win so I trained hard, but I never had the head for it. For me, it became more about using it as a tool to motivate me to get strong for outdoor climbing. If you’ve got the head for it and you enjoy it, it can be great for just that. It also gets you into the scene, introducing you to all the young crushers. It’s a good community-building thing.

You excelled at sport climbing during your early career, making the first ascent of the USA’s first 5.15a/9a+ back in 2003. Do you still have an interest in hard sport climbing?

I love sport climbing. I got sidetracked on El Capitan for 20 years, but I’m back at it as it’s a little easier with the family. I still love it, and I’m sure that I’ll continue to do it throughout my life, but it’s not what I get obsessed about in the same way. It’s good training and it’s enjoyable but I don’t get totally obsessed like I do with big walls.

You write eloquently in your book about the subtleties of dancing up vertical rock, as opposed to wrestling with steep overhangs. Is this a style that you have always had an affinity for?

When I was a little kid we climbed on vertical granite; overhanging rock climbing didn’t really exist when I was really young. We went to places like Vedauwoo, and I learned to climb cracks there. Everything was vertical. I remember the first time I saw an overhanging sport route and the quickdraws weren’t hanging against the wall and it was the craziest thing to me.

You are perhaps best known for your big wall free climbing. What drew you to this aspect of the sport?

I went to Yosemite every summer as a child with my family, and I’d watch my dad climb El Cap occasionally. I knew about the dirtbags in camp four, and Warren Harding (an early big wall climbing pioneer) had been to my house. It was in my focus. It seemed like the right thing to do; it was a combination of all of my skills and aspirations. I was a pretty strong climber but not the best, and I was pretty adventurous and pretty tough in the mountains, and it combined those things.

Free climbing on El Capitan has boomed in recent years. How have you seen the big wall free climbing scene change?

It’s pretty cool. Back when it started, there was one free ascent every five years, by people like Todd Skinner, Paul Piana and Lynn Hill. The Huber brothers came, and they were sport climbers, and I was a sport climber at the time, and that clued me in to it. Then, for a decade, it was just me and the Hubers, and I was like, ‘This is the coolest thing in rock climbing,’ in my biased opinion, ‘Why are we the only ones doing this?’ Eventually it caught on, which is really cool, and now sometimes there’s 10 free climbing parties on El Cap at one time. It’s super exciting; now you go to Yosemite and you’re surrounded by everyone working on their projects, sitting around in camp four discussing their big adventures.

To persevere for so many years on the Dawn Wall project you must have thoroughly enjoyed the process, but were there times when you doubted success, and how did overcoming earlier adversity prepare you for this?

Definitely. I think that climbing has taught me to not fear failure that much, because most of the time in climbing you’re just failing over and over again. I think at some point I realised that the goals I had were just a focal point, a motivating force to get me out there every day, and getting out there every day is what I love the most. I like the growth, and I like the life experiences, the camaraderie and the brotherhood of being up on big walls.

Climbers sometimes find that they feel lost after completing a major project, as the single focus of their time and energy is removed. How did you feel having completed the Dawn Wall, and how did these emotions change over time?

I’m so goal focussed and I love having these big projects driving me forward, so I think when the Dawn Wall happened I probably would have gone through a bit more of a low, but life was so hectic suddenly. I was going all over the place doing interviews, and the media thing was just weird and kind of crazy, and then I decided it was time to write a book. I approached that in the same way I approach a climb – I delved down and got kind of obsessed with it, trying to make it as good as I could.

How was it dealing with the mainstream media attention and focus that came from the Dawn Wall?

It was super bizarre. I’m a very reluctant public figure, I’ve never been that comfortable in front of a crowd or in front of the media, but I began to get used to it and even to appreciate it in some ways. It’s fun to spread the excitement of climbing and it was great to see that. In terms of being in front of the camera, it’s still stressful for me. I’m getting a little better at it because I’ve gotten some practice now, and its one of those things where I’m like it’s a good skill to develop.

You recently met with members of Congress to advocate for the better management of public land for recreational users. Are you using your renown to try and do good within the climbing community?

I don’t know if that was my initial intention, but the Access Fund and the American Alpine Club organised the event and they invited a bunch of us climbers to use our notoriety to promote climbing, and it worked. We went to DC, where we met senators like Senator Kaine, who was a heartbeat away from being the Vice President of the United States. He came to the meeting because he wanted to meet Sasha (Digiulian), and people like Senator Bennet were there and they wanted to hang out and talk about climbing. It did clue me in; climbers have a voice now, which is kind of crazy. I’ve experienced climbing go from this very dirtbag culture of a group of vagabonds to going to DC, and that’s kind of a crazy thing. Also, in the climbing community in the US, there’s a big lash back now against the Trump administration, it feels like everyone’s gung ho. When I mention public lands lobbying at my slide shows, it gets the biggest cheers, which wouldn’t have happened a few years ago.

Has lobbying for access to public lands become a big issue recently?

I think until now access was taken for granted. It didn’t feel like a big threat for the most part. We were like, ‘Oh yeah, of course we get to climb here, we have all of these public lands’, but suddenly it feels like there’s a bit of a threat.

Moving away from Yosemite, you’ve done some impressive big alpine link-ups down in Patagonia with Alex Honnold, including the first ascent of the Fitz Roy Traverse. How did that come about?

I’d gotten together with Alex when we were both in Yosemite, and he talked me into doing some big link-ups there first. We got along super well and it worked well. We had our systems which worked well together. I’d had the idea of going to Patagonia, and traversing the ridge had been a pipe dream. With Alex, we were linking up these big walls in Yosemite in no time at all, so it seemed like a good thing to try. It was an amazing trip.

It seems like the logical progression, having climbed these hard big-walls in Yosemite, would be to go down and try routes like Eternal Flame on the Trango Tower in the Karakorum. Do you think that you will try routes like that?

Possibly. I think that the more alpine stuff is right on the verge of what I will tolerate in terms of risk, especially now I’m a dad. I have to balance that. It’s very appealing, as in some ways I think that’s the style of climbing that suits me most, even more than big walls. I love it, but I’ve really not got to die.

It’s interesting that you mention that your risk tolerance has changed since becoming a father. Is that a process that you have been aware of happening?

Yeah, I think about it all the time because my risk tolerance in the moment is exactly the same. You’d think that in the mountains, having a kid, when scary things happen I’d be like, ‘Oh god, I have to get home to my kids,’ but it’s not like that. I’m always like, ‘Whatever, it’s fine’, so I think I have to think about it from afar, choosing what kinds of climbs to go for and what not. If I didn’t have a family, for sure, I’d be going to the Himalaya, travelling all over the world for big wall adventures, but not only is it risky but also it takes you away from home life for long periods of time.

And sometimes you don’t get to do very much climbing?

Yeah, I don’t mind that. I like going to a remote place and sitting in my sleeping bag and reading books for a couple of weeks. I’m okay with that. It’s more that my kids are so cute right now; they’re at this amazing age and they want daddy around, so I feel like I’ve got to

be around.

Moving on, how did you go through the process of writing your book?

I’d been a contributing editor for Alpinist magazine and I’d written probably 20 articles over the years for them and magazines like Rock and Ice. I felt that whilst I wasn’t a great student and a great writer when I was young, writing for Alpinist had developed my skills. I’d go on these amazing trips and write about them, meditate on them from different perspectives, and I recognised that I had a good story to tell and figured that I would write a book someday. Then the media thing happened after the Dawn Wall and I was like, ‘I could probably sell it now,’ so it seemed like a good time to do it. I figured that I would wait until I was an old man originally, but after the Dawn Wall I had this format in my head, and I was like, ‘This is pretty powerful; this could be a really good book.’ I sat down and started writing it, and there were all of these literary agents emailing me. After the Dawn Wall, I could connect with this New York community, so I went and sold it, and got a great team. I still didn’t know how to write a book, I attacked it, did mountains of research, called up Jon Krakauer (author of Into Thin Air) and Jim Collins, and then I found a good partner in Kelly Cordes.

Kelly had already written books like ‘The Tower’, right?

Yeah, he was my next-door neighbour, and he’s a great writer. When I wrote the book, I didn’t want to be interviewed and then have someone else write it. I was like, ‘You don’t hire someone else to climb a mountain for you.’ I wanted to take the journey and learn about it. I thought that the book would be better and would be deeper, as it’s hard to get deep in an interview. So I got behind a computer and started typing. I got so obsessed that I would spend thirty or forty hours a week working on the book. I blocked out time and treated it like a full-time job. I would write the chapters as well as I could and then work on them with Kelly to shape and strengthen them, in the same way that I had worked with editors at Alpinist and Rock and Ice. I think Kelly maybe got more than he was bargaining for; it ended up being a lot of work for him as he got set on it too. We constantly worked on it together, wrestling with it. It was amazing, he’s my best friend and therapist now. It was an incredible process to go through with him.

You write very honestly about sometimes difficult personal relationships throughout the book, particularly those with Beth Rodden and your father. Was this a comfortable experience, and were you concerned to be exposing your inner life to public scrutiny?

It was pretty easy actually. I just felt like I had to. I guess I’m pretty bold with that kind of stuff. Maybe that’s from climbing, but maybe also because of my experience in Kyrgyzstan when I was younger. There was this guy from the north-east, John Bouchard, who tried to villainise us, and spent two years of his life trying to prove this conspiracy theory about us. After feeling vulnerable and feeling mad, at the end I felt like there’s always crazy people out there who will try and tear you down no matter what you do. You can’t focus on that, and the fact that I’d been though that made me think that if I wanted to make the book as good as it can be, then I have to be absolutely vulnerable. Kelly was good at pushing me in that direction. It is a bit unsettling in a way as the book goes out into the world, I’m like, ‘Wow, the deepest depths of my soul are exposed,’ but it seems that people appreciate that. Climbing descriptions are kind of boring after a

while so I tried to reach a balance – good for the climbing but also really relatable. And plus, a lot of

those relationships I just needed to process for myself. I needed to sort them out and writing is a good way to do that.

Where did the name come from? Part reference to psychological drive and part tongue in cheek reference to Kyrgyzstan?

It was all those things. The first words I wrote when I sat down and started typing, I went straight to that time in Kyrgyzstan when I pushed the guy. We always referred to our Dawn Wall attempt as the final push, going for the ground up ascent, so it was really those two. The motivational side of it, when we came up with the title and the sub-title struck me differently and now I’m not sure if we hit that right. Maybe it sounds a bit too self-help motivational type title, and the book is supposed to be motivating, but I didn’t want to stuff that down people’s throats.

Where do you think that your climbing will go from here?

I think I’ll continue doing similar stuff. I’ll go on an expedition a year and I’ll go to El Cap. My campsite is booked for this autumn in Yosemite, and, at least for the time being, I’ll bring my family with me, which is great. It’s a good way to live, dragging them all over the world; they seem to like it. But I also felt like I needed to diversify a little bit. You can only use your fingertips so much. I wanted to use my brain and I wanted to learn how to be a story teller.

Have you been tempted into the motivational speaking industry by the Dawn Wall fame?

I’ve realise that outside the climbing industry, companies don’t want that. They want the clichés, and I’m very bad at the clichés; I just roll my eyes. Sometimes I can walk the balance of trying to find what feels genuine to me. If I could figure out how to do that effectively, I would be totally into it, because you do come out of those events speaking to people who have such totally different lives. It’s almost easier to inspire them than to inspire climbers, so I’ve found it kind of fun. One of my main mentors is this guy Jim Collins, and that’s his world. It’s amazing watching him. People’s minds are blown. He’s such a good speaker and I aspire to be like that, but I don’t know if I buy it as honestly.

You mention in your book that you’ve spent so much of your life having these experiences in climbing and learning from them, and that you now want to give a little back to people. What form do you think this will take?

Right now, I’m going in lots of directions and seeing which of them sticks. There’s the public land thing; there’s mentoring people like Kevin; there’s generally spreading the stoke for climbing. I think climbing is incredibly uplifting and a great way to live, and helping to perpetuate that is important. Climbing is a way to do that, but learning to tell those stories is absolutely crucial as well.

‘The Push’ is available now on Amazon and other booksellers. For more info on Tommy Caldwell, go to www.patagonia.com/ambassadors