As Lowe Alpine celebrates its 50th anniversary, Dan Aspel talks to the brand’s former ‘chief gear tester’, the legendary Jeff Lowe…

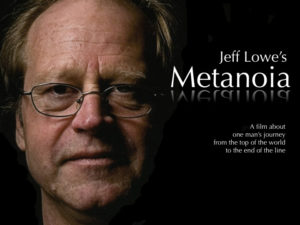

Plenty of outdoor brands have been founded by enthusiasts, but Lowe Alpine boasts a backstory that must surely be the envy of most. A family from the wild open spaces of Utah. A lively home life populated by two parents and eight siblings. A father whose passion for mountaineering inspired three of his sons to ever greater heights. Cottage industry backpacks that would go on to redefine outdoor gear on a global scale. The emergence of one of the most important figures in the world of mountaineering. A new, direct line up the Eiger’s Nordwand. The 2014 film ‘Metanoia’ which immortalised it. The advancement of ice climbing, dry tooling, and the means with which people could pursue them. There’s very little in the realm of climbing and outdoor innovation that can’t be found in the Lowe family scrapbook. And, as 2017 marks the brand’s 50th year in business, what better way to learn more about it than to speak to the man who was directly responsible for many of those great achievements, and whose efforts made many of the rest possible?

Jeff Lowe is, if you’ve not heard the name, justifiably regarded as one of the most influential mountaineers of all time. This is the guy who was a leading light of American climbing from the 1960s to the 1990s, who pushed the limits of alpine-style soloing in the Himalayas and most notably on Ama Dablam (1979), who was a pioneer of ice climbing and a devoted gear tester who helped create the equipment necessary to enable a whole generation of limit-pushing enthusiasts. Jeff, 66, now lives in Lafayette, Colorado with his partner Connie Self. He doesn’t climb anymore, although that’s not through choice. It’s because, in 2000, Jeff began to experience issues with balance and coordination. They have become more severe as time has passed and, after years of attempted diagnosis, his current condition is accepted as “an unknown neurodegenerative process” similar to MS or ALS. Jeff’s disorder, in a cruel irony, is much like the man himself: one of a kind. I therefore approach my interview with him with a small amount of trepidation. As Jeff’s ability to speak has been severely affected by his illness, will I be able to understand his answers? Will I offend him if I don’t? Will my questions seem tiresome or inadequate given the amount of physical adversity Jeff must surely face on a daily basis? It turns out I needn’t have worried.

Although Jeff may need total physical care, it’s hard to imagine a more inspiring, positive or generous interviewee. Or even a more eloquent one. Between his letter board, through which he can spell out words and sentences, Connie’s seemingly total knowledge of his history and opinions, a large number of pre-prepared answers, and the effortless interaction between the two that at moments gave the impression of interviewing not two but a single person, learning more about Lowe Alpine, the family behind it and Jeff’s own climbs and ambitions is as easy as it is pleasurable.

Era of legends

I start by asking Jeff about the era in which the brand was born – a time in which marques like Chouinard, Salewa and Edelrid were among the most commonly known to American climbers, and even then far more esoteric in scale than they are today, the stuff of a small cadre of dedicated hobbyists rather than the mass market. “In the 1960s there wasn’t a lot of manufactured gear to choose from,” says Connie, “and people like Jeff, and his brothers Greg and Mike were constantly having to make do with whatever was available, with their minds always wondering how to do it better. And they’re still doing it. Even when Jeff first started using a cane and then a wheelchair. It wasn’t long before they’d come up with ways to improve all the medical equipment in the same way as they had with climbing gear”.

To explain this fearless ability to re-think kit and equipment which, it’s fair to say, most of us probably lack, it’s important to trace the family history back a little while. To begin at the beginning: “Dad was born and raised in Ogden,” recalls Jeff. “He began life as a Mormon but was an early atheist convert. He was a land lover, a water lover, a people lover, a builder, a hiker, a skier… and a hundred other things besides. He encouraged us to keep a menagerie of every animal we could find, even wolves and bears. That kind of person makes for an incredible kind of family.”

By all accounts, Ralph Lowe was possibly even more impressive a figure than Jeff recalls. It was in 1934 that the then Idaho resident, aged just 16, first made the pilgrimage to Wyoming’s Grand Teton range. Chief among it is the 4,199m mountain from which the surrounding national park takes its name – a many-ridged giant of alpine beauty riddled with classic lines. An easy object for any mountaineer to fall in love – or into obsession – with. And, although his passion for climbing took him even further afield (family lore has it that he once drove a 1,600 mile round trip in a single weekend to climb Washington’s Mount Rainier… in a storm), Ralph became a lifelong visitor to the peak and its surroundings, exploring its routes and summits often over the next 30 years. It was only natural that his children, and climbing enthusiasts (Jeff, Greg and Mike in particular) would want to join him on future trips.

Early years

As early as 1956, Ralph first took Mike, at 10 the eldest, up the exposed and technical Exum Ridge of the Grand Teton. Two years later, he returned with eight-year-old Greg and seven-year-old Jeff. This made Jeff the youngest person ever to complete the climb, a record he held for many years afterwards. But it came at quite a cost. “I really enjoyed the climb,” says Jeff, “even the scary step across a big void from the Broadway ledge to get onto the ridge. On the summit, I thought I could see on the horizon the curvature of the earth. But on the trail on the way down, I fell and hit my head. It bled a lot and it scared me. I had nightmares for several years after that and found other sports like judo, gymnastics, little league baseball, and especially ski racing, that filled my time.” But the desire to climb inevitably reasserted itself. By the time Jeff was 12, the yearning to experience steep rock once more “overcame everything.” Within a few years, the trio of young Lowes’ climbing abilities surpassed those of their mentor. “That might have bothered some fathers,” says Jeff, “but he was always excited about it. He always encouraged us to do what we wanted, absolutely no limits. He really trusted us.”

Ralph and his wife Elgene raised a total of eight children: four boys and four girls. The family home was found in the small crossroads city of Ogden, Utah, which sits on the narrow strip of land between the Wasatch Mountains and Great Salt Lake. The family could boulder and climb right out of their back door. It was every bit the outdoor Eden it sounds. And even though not all of the children went on to become famous mountaineers, every one of them remains a skier to this day. Jeff’s sisters in particular, he tells me – all now in their 50s and 60s – still ski their way through the winters. A love of the outdoors was inherent in the Lowe household.

“We went camping from my earliest memories,” recalls Jeff. “We rode horses on our ranch, we had campfires and cooked outdoors. We went canoeing and hunting. I loved it all.” And discovering the ever grander landscapes of the Tetons and other ranges proved a rich source of inspiration. “I was fascinated by the way landscape changed as we hiked up through thinning pines into the alpine zone of moraine and snow, furry marmots and the sounds of gurgling run-off water and sharp pika squeaks,” says Jeff. “Craggy peaks our inspiration; alpenglow and a can of beans at high camp, the Milky Way and a billion points of light in the frosty night. A pull of water from the canteen and a banana on cold, pre-dawn starts. It was all an adventure and I was hooked from the get-go.”

Given their surrounding environment, and the opportunities afforded them by their father, it’s little wonder that Mike, Greg and Jeff would prove to be naturally talented climbers of unusual dedication. That might also be something to do with the company that their father kept: “We grew up meeting and climbing with guys like Royal Robbins and Yvonne Chouinard,” says Jeff of the visitors to the local climbs, and thus the Lowe household, throughout his youth. “Just being around these famous climbers and designers made their kind of attitude and behaviour second nature to us.”

It therefore wasn’t long before the Lowes’ skills outstripped the equipment available to them. And, for Greg in particular, this represented an opportunity. Some of his many childhood passions had included the common enough challenges of building telescopes and model rockets, and the less common activities of playing with chemistry sets and fashioning his own gunpowder. They were hobbies that even saw a seventh-grade Greg win second place in the Utah State science fair. Consequently, when he turned that energy and ability towards inventing outdoor equipment, the results were numerous and impressive.

Birth of a brand

Starting with the co-founding of the Lowe Alpine brand in 1967 (a family business initially run from his parents’ basement in Ogden), they would go on to include the first ever portaledge-style tent and curved ice axe, the first use of plastic buckles, and the creation of the now-ubiquitous ratcheting ice screw. But chief among them all may just be the Lowe Alpine Expedition Pack. Built in the year that the company began, it was the first backpack that utilised a flexible internal frame, a chest strap and side compression to create the concept of load carrying technology. Ably facilitating the carrying of heavy climbing gear into the high mountains, it remains one of the great innovations in outdoor gear history.

The Lowe brothers also formed something of a dream partnership in this respect. While Greg’s climbing achievements shouldn’t be underestimated (he was, for example, the first ascensionist of the huge roof of the Macabre Wall – a challenging route near Ogden that remained unrepeated for 20 years), it was Jeff who took on the role of chief gear tester for the business. He would take new developments out into the field and give direct feedback, the fact that he was both co-designer and the intended end user making for a uniquely effective mindset.

So who got the best deal out of this arrangement? Greg at the workbench or Jeff on the cliff-face? “I would say I did, Greg would say he did,” Jeff tells me with a smile. In response, I can’t resist the chance to ask Jeff for his all-time favourite piece of outdoor gear. The answer’s an interesting one – the tricam. Invented by Greg in 1973, it’s a kind of a hybrid between a nut and a cam. Although a little more difficult to place than a spring-loaded version of the latter, it’s a lot cheaper, considerably lighter, immune to deep cold and an elegantly simple way to protect yourself in a mixed climbing environment. In Jeff’s words, “You can use it in so many situations.” Which is handy, because in his career, Jeff probably found himself in every single one that a climber could.

“I started to form this idea of a progression of climbs that would lead up to doing some of the harder and more beautiful routes on the highest peaks,” Jeff says of the early days when his climbing really began to happen in a big way. “It must have good rock, great technical difficulty, be long and sustained, and, most importantly, take an elegant line. I needed to do climbs that are at my limit, or even a little beyond, so that I have to rise to the occasion. Otherwise, it’s just another climb.” It was a philosophy that would lead naturally to the world’s highest mountains in the Himalayas, and the uncompromisingly self-reliant, unsupported alpine- style of climbing.

When I ask Jeff where he’d consider his spiritual home in the mountains to be, his answer is certain: “The Canadian Rockies – the Icefields Parkway. It’s so vast and varied: rock, ice, alpine climbs… and peace. It’s not a well-travelled place,” he says. His relationship with the region was well-known when he was climbing in his prime. Connie tells me of one memory Jeff shared with her of walking into a local bar on one climbing trip and finding the whole place abuzz. The reason was simple – people had heard Jeff was coming and most were afraid that he’d take all the first ascents they’d carefully planned for the season before they got the chance.

But although Jeff’s career eventually went on to reach a reported four figures of first ascents (truly great climbs, such as soloing the south face of Ama Dablam and free climbing Pakistan’s Trango Tower in Pakistan, and all in a rigorously independent style), it’s heartening to hear that there was still a huge amount of support from Family Lowe. Greg, Mike and Ralph were there with Jeff when he climbed Ama Dablam. He may often have been alone on the rock, but he was rarely alone in spirit.

Dream peaks

Conscious that it could make for a difficult question, I ask Jeff if he could wake up tomorrow and climb any mountain, anywhere, in any style, which one would it be? The response is immediate: “The west face of Makalu. Direct, alpine-style, and solo.” It was in 1993 that Jeff last attempted exactly that feat, being avalanched off too late in the season to make another attempt. It remains unclimbed today, unapproachable to all but the most dedicated and accomplished mountaineers. It’s clear that failure, or the threat of failure, has never threatened to derail Jeff’s mindset and ambitions.

It’s that confidence and yearning for the greatest of challenges that explains Jeff’s most famous climb of all, his 1991 winter solo of a direct route up the Eiger’s north face. Named ‘Metanoia’ (an ancient Greek word literally translating as ‘beyond perception’ and used to denote a profound change of mind or attitude), it remained unrepeated until December 2016. Intending to honour the achievement of 1938’s original climbers of the infamous Nordwand and the hardships they faced, and struggling with his own personal demons at the time, it was always destined to be a climb of consequence. “Even to approach that level of commitment,” Jeff says of the pioneering team’s ordeal, “I had to stack the deck against myself: go alone, in winter, without bolts, and try the hardest unclimbed route I could find on the highest part of the wall.”

This led to a life-changing experience. “After days of small rations, the space between my belly and my backbone contained nothing of substance to prop me up,” says Jeff. “Shivering in waves, I stared at a picture of my two-year-old daughter, Sonja. I felt remorse for the mess I’d made of my marriage and the sense of abandonment that she would face. My awareness detached itself from my body. I could focus on any place or time and instantly be there. My soul took me to the farthest reaches of the universe and back. The clarity of sight, hearing and consciousness was like nothing I’d ever known – beyond words. I experienced a fundamental change of thinking and an opening of my heart.”

This revelatory moment is explored in great detail in the 2014 film ‘Metanoia’, a piece of work that’s as much a moving human story as it is a celebration of climbing. And, in many ways, it’s only thanks to that single flash of insight, and the tragedy of Jeff’s physical decline, that he ever slowed down enough to accept what he’d already achieved in life. In Connie’s words, Jeff’s climbing was always “very personal, and always done for his own reasons and to fulfil his own visions. His reputation was never on his mind. He was simply never satisfied with what he’d achieved. Not until he was forced to stop and look back.”

Not that he’s struggled for recognition in his career. In 1986, Jeff was given the American Alpine Club’s Underhill Award for outstanding mountaineering achievement. He didn’t, however, attend the ceremony. So how does he feel about winning the much celebrated Piolet d’Or Lifetime Achievement award in 2017? “It’s the consummate award,” he says, indicating that his attitude towards professional recognition has softened somewhat, “and most of all, it’s humbling to be on a list of lifetime achievement in the world of climbing. It gave me the chance to reach out to the whole tribe and say, ‘Here you go, it’s your turn now, so go out and do it!’

“It has also meant that a lot of today’s best climbers – Ueli Steck, Steve House, Will Mayo, Conrad Anker, Thomas Huber, Tommy Caldwell – have made a point of searching me out so they could talk about climbing with me and let me know that I’ve inspired them along the way. It’s great to have that relationship. And it’s not just professional climbers; I get emails from enthusiasts all the time. One couple got in touch to say they wanted to repeat every one of my climbs in Zion National Park. There’s a lot of love shared. It’s a real ‘love fest’!”

If there’s any sense of sadness in Jeff at handing the torch over to the next generation, and in hearing of great climbs that he himself cannot hope to be involved in, then it’s not apparent. “Every day is an adventure now,” he says. “On a deep level, my life is so very interesting and worthwhile. Again, something I learned from climbing is that it doesn’t have to only be fun to be worthwhile and rewarding. These days, I am often asked if it doesn’t feel especially unfair to be stricken in this way when my life was so centered on the exact physical and mental abilities that are now so diminished, or completely gone. Although I do miss those things, instead of feeling bitter over the loss, I can’t help but be forever grateful for the gift of fifty fantastic years. Whatever time I get from here on is gravy. I’ll continue to ‘Have fun, work hard, and get smart’ to the best of my abilities.”

It’s hard to expect anything less from a Lowe.

Visit www.jeffloweclimber.com where you can arrange a screening of the superb documentary, ‘Jeff Lowe’s Metanoia’, in your own town. This, and direct donations, can help support Jeff and contribute to his ongoing medical care.