As the film ‘In Constant Motion’ is released, Kev Foster talks to Arc’teryx athlete Adam Campbell about the accident that nearly wrecked his career and the hard road to recovery…

Adam, your reputation precedes you in the world of ultra and mountain running; how would you describe yourself?

“I’d describe myself as a mountain athlete who’s primarily focussed on ultra endurance challenges; my real pleasure comes from moving through mountains in a light and fast way, and trying to cover as much ground as possible under my own power; I get a lot of pleasure from that. I moonlight as a lawyer on the side.”

Could you tell me more about your background in sport? How did you discover the world of ultra and mountain running?

“I actually grew up in Lagos, Nigeria, which is about the flattest city in Africa. It’s on the beach, so it’s a far away from the mountains as you can imagine. Both my parents are Canadian, though. From a young age I was really into reading adventure stories and got really drawn towards mountaineering stories; so the history of mountaineering has influenced me from a young age; and I just loved the sense of adventure. When I moved to Canada at around age 17, I started to focus my sports a little bit. My first triathlon happened to be the Canadian Junior Triathlon Championships and I made the Junior Canadian Triathlon Team. Then I got invited to compete at the World Championships for Canada, and from there I became a professional triathlete over a couple of years. That got me training a lot more seriously and I competed internationally for Canada.

“I was trying to qualify for the 2008 Olympics and, for whatever reason it was at the time, it seemed like the longer the runs the better I did relative to my friends, so I started to focus on running. I was living in Victoria, British Columbia, which is quite a beautiful place with beautiful parks and we’d run a lot on trails because it’s a little easier on your body and its just nice to be on trails. As I got more into the Ultra scene and my runs became more technical, I started picking up more mountain skills. That led into more climbing, which led into more backcountry skiing, and so slowly my skills developed and I discovered more efficient ways of moving in the mountains. This allows you to explore new areas.

“Living in Canada for six months of the year throwing on a pair of ski touring skis becomes a much more efficient way of still pushing yourself; and as ridges get pointier here, it probably becomes wise to rope up for them, so you have to start developing some rope skills and that opened up a whole other area for me; you’re not restricted to running on trails and racing; you can look in a much broader way of applying your fitness and combining it with some technical capabilities, and that the was the direction I was going as I had my accident.”

Between 2014-2016, your ultra-running career was on an impressive trajectory. Mixing it really well with the likes of Kilian Jornet, finishing 3rd in the 2014 Hardrock 100 and winning numerous other ultra distance races. What were the most influential factors in your consistency and performance during that period?

“By that point I’d been doing Ultras for about 5-6 years, so I think I had finally built up enough mileage in my body to really be able to handle them. The competition did drive me to a certain degree, I liked picking competitive races and I liked picking challenging courses, because they scared me into staying motivated to train. The Hardrock course specifically just really inspired me; it’s so beautiful and that 3rd place finish was a huge surprise for me; I did not expect to be able to do that well.

“By that point I’d figured it out; basically in training and preparing for these things you’re working on your bag of tricks, how to manage yourself properly through long races, how to eat properly, the little psychological games you play, “the self-talk”. You’ve built up a big enough repertoire at that point that if you can just use those tools you’re likely to have a good race. I had really good flow through all the races. I also tried not to race too much, because I really wanted racing to be special and when I showed up at an event I wanted to be really well prepared and be excited to be there.”

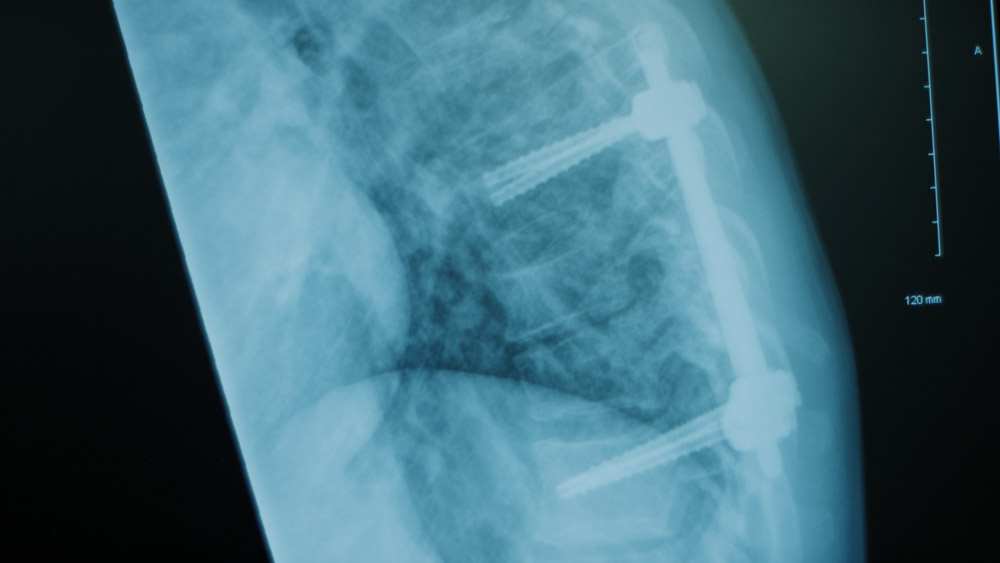

Some of the metalwork inserted into Adam’s body after his accident

On 30th August 2016, you took on a big challenge with a couple of friends and you were involved in serious accident. Can to briefly describe the route you were attempting, the nature of the accident and the injuries?

“We were trying to do something called the Horse Shoe Traverse in Rogers Pass, in the Selkirk Mountain range of eastern British Columbia. It’s the birthplace of mountaineering in Canada. We were trying to link up 14 peaks; it’s this big horseshoe and you’re travelling along ridges the whole time or across glacier. It’s not a trail run, it’s a mountaineering push, and the fastest time we’d seen anyone do it was about three days.

“I was with Nick Elson and Dakota Jones who are both unbelievably talented mountain athletes; I mean, Nick’s a certified guide, an incredible rock climber and just an all-round mountain badass, and Dakota had been dominating the mountain running scene for a long time. So we thought that we were capable of doing the push in a single day; and you know a day could be 26-30 hours, but one big push essentially. Its only about 55km but its got around 8000m of elevation gain and as I said, you’re not on a trail at all; some of the classic 50 climbs in North America are there so you’re talking proper climbing.

“We left around 6am; we were moving super efficiently as a group and we were on pace to doing the traverse in the sort of time we thought we might be able to. Nick and Dakota were just ahead of me up a tower; maybe like 400m; and we were about 2/3 of the way up and all of a sudden I felt this rock pull out on me.

“It was an horrendous feeling; I started feeling myself tumbling backwards; the buttress is a series of ledges and I started tumbling from ledge to ledge; my feet would pass over my head, so I was cartwheeling and somersaulting down these series of ledges; it’s was a really strange feeling; I was conscious through the whole thing and I was positive I was dead because I just kept falling and I thought eventually something is just going to kill me. After tumbling for what felt like forever, I suddenly stopped falling and I was face down in a pile of scree. I just saw this pool of blood below me; I remember instinctively not liking seeing that and pushed myself up onto my back, rolled myself over, and instantly was like, that was a really bad idea, there’s a lot of blood, don’t move.

“If you’re going to have a big mountain accident, have two of the fastest mountain runners in the world with you. Nick and Dakota, who watched me fall started making their way down towards me and they were convinced they were coming for a body retrieval; because I’d fallen over 60m. For most backcountry trips in Canada there’s no cell signal, but in this one particular spot you’re close enough to the road still that from the top of the previous peak we noticed there was a cell signal. Dakota stayed with me, put warm clothes on me; we had a space blanket and down jackets; Nick grabbed the InReach, pressed SOS on it and ran up the previous peak to call the search and rescue crew and describe exactly where we were.

“We had waited for perfect weather to do the traverse; we wanted to make sure we had a 2 or 3 day weather window just in case something did happen; luckily the search and rescue helicopter crew was actually patrolling the area looking for unexploded avalanche bombs, so not very long after having my accident, probably within half an hour they actually flew over and located us. I was in and out of consciousness this whole time with the pain and the shock. They had to fly 80km back to Revelstoke to get a different pilot and crew because where we were they weren’t able to land. Within an hour and a half of my accident they’d flown back and I got carried away underneath the helicopter. They flew me out to the highway, where a “medivac crew” was able to do a proper assessment and start treating me; I then got flown to Camloops which is 300km away and is the closest trauma centre.

“I had deep lacerations, down to the bone across my whole lower back; I was wearing a backpack with a rope in it, which protected my spine a little bit, but I’d broken some vertebrae; I’d broken the top of my hip bone and I was just bleeding from everywhere; from my head, I literally had stitches between every single knuckle, lacerations all across my body; they stitched me up completely; then I came through a few hours later.

It’s ridiculous to talk about lots of luck in a serious accident, but it sounds like you had one bit of bad luck and a hell of a lot of good luck.

“Yeah – I really was lucky in quite a few ways; you know the injuries I had were horrendous but for whatever reason, due to nothing that I did, just sheer dumb luck with the way that I landed, I didn’t damage my spinal column; there was a little bit of nerve tingling; I couldn’t feel my legs for a bit but that has obviously come back; I should be paralysed, I should be dead, really. You know I was bleeding a lot, so if it had taken a few more hours to get to me its quite possible I would have bled out.”

As somebody who’s also had significant long terms injuries before, although absolutely agonising physically, I found the mental side of injury was almost harder to deal with; How was that journey for you? Did you think at some point that you wouldn’t be able to run again? How did it play out in those initial days, weeks and months of recovery?

“You go through a lot of stages, … I did ask the doctor when I first came out, “what does this mean?”; he said “You’ll probably be OK. Your surgeries all went really well”. But I wanted to know what it actually meant; will I be able to walk a little bit, will I be able do some light jogging, or will I be back at the level I used to be at? I think because as I was falling I was convinced I was a dead person, the actual performance side of my recovery was never important to me; just to be able to move and get outside, that took on everything. The other thing was that I was quite mad at myself, because I realised that I’d impacted a lot of people; my accident went so far beyond just me. It impacted my family and friends. I struggled with that quite a bit at the time as well.

“I realised really quickly that I had to celebrate anything I could do; so 1 step, then 2 steps, then 50 steps; then I’d get a huge setback and not be able to get out of bed for a couple of days; I just accepted that was all part of the recovery process. I just tried to be kind to myself; there was no point being mad, upset and sad. I allowed myself to have those kind of emotions, because it’s all part of the process, but not to dwell on them. I realised, it’s just like running a 100 mile race; you go through these huge highs and lows and you just have to accept that’s how you’re feeling at that moment, but it will pass. The more positive you can stay, the better your feeling overall is; I worked hard to find some joy in this overall shitty situation.”

It seems you appear to have made a pretty remarkable recovery; to go on to run the Hardrock 100 again less than a year after the accident. I looked it up, you came 31st; it absolutely boggles my mind that less than a year after an accident of that nature, with those serious injuries, that was possible; its hugely inspiring and I wonder how you feel about that? Is it something where you just decided, I am going to do this, I’ve got to do this? How was it?

“I literally signed up for Hardrock in a hospital bed not able to walk; you have to put your name in for a lottery, so I thought ok, I’ll sign up for this race. At the very worst I’ll get pulled and we’ll figure it out from there; I’ll start doing some activity and if for whatever reason I’m not able to do it I’ll just withdraw and nobody’s really going to hold that against me.

“Ski touring through the winter was one of the first activities that I was able to do, because it was quite gentle on my body. Skinning uphill was fine; skiing downhill was definitely not the prettiest skiing I’ve ever done. But it was just so incredible to be back out moving in the mountains;

“The snow started to melt and I started to increase my running miles a bit, the running did not feel great; like it hurt! There was now a huge hitch in my stride, that previously felt really fluid and dynamic. I was learning how to move with my body again. I figured the more I used it, the more it was going to start moving in a better way. The big question mark for me was what would happen to me physically after 10, 12, 14, 15 hours of moving. I didn’t know what was going to happen at that point.

“When the Hardrock came round I felt I had done some pretty good training; obviously I know how to manage myself and what I need to do in terms of nutrition; So the race warning went off and despite telling myself I was just there to enjoy the day, I took off with the leaders like I had always done and from there things changed quite a lot for me. It was a strange day.

“So, the gun goes off and I take off with the leaders; chatting with Kilian Jornet and Mike Foote, feeling pretty good; but everyone feels good 10k into a race. Then all of a sudden about an hour and a half into the race I started to not feel quite so hot; the top guys started running away from me and I really struggled with that mentally. It really broke me. That was the first time when I got really sad. I felt a big sense of loss at that moment.

Adam at the start of his ‘comeback’ Hardrock 100

“As I was moving along, literally walking and crying, Anna Frost, who’s one of the top female ultra runners in the world and a previous winner of the Hardrock saw me crying. She stopped and gave me this huge hug and said, “Adam its ok, you don’t have to do this, you have nothing to prove to anyone” It was really special to have her tell me that; it gave me this allowance to keep going in a slightly different way. So I tried to do that and to appreciate this beautiful terrain, and felt really good until about 60 or 80k into the race.Then all of a sudden running downhill through this really rocky section something happened to my foot and it was just sheer agony. I wasn’t sure what had happened; I thought I’d broken my foot. For the next 80k I basically walked. Once again I had this big negative self-talk. I just wasn’t enjoying the experience at that point. I got really emotional, I cried a lot. In retrospect, I was just letting go of 10 months of fears; it was the first time I’d really grieved my accident.

“So, classic ultra, you’re just putting one foot in front of the other and the miles tick by; eventually I rounded a bend, crossed a river and I was about two miles from the finish. That was the first time where I actually believed I was going to finish; at mile 98. When I came into the town all of the previous finishers came to the finish line to cheer me on; that was incredibly emotional for me and I just cried for hours. I was emotionally and physically exhausted at that point, but also so filled with love and pride, that was a really special moment, but I can’t say I particularly enjoyed much of the previous 33 hours!”

What concerns you the most when you’re taking to the mountains and what sort of strategies do you adopt to mitigate them? Has your accident significantly changed your process with regard to that?

“It definitely has. Since my accident, I’m actually more comfortable doing very technical climbs, where you’re roped up and protecting quite a bit more; this as opposed to scrambling and things with exposure like what I was doing when I had my accident.

“Since the accident I’ve been doing lots of mountain lessons. I’ve done really advanced avalanche training courses, I’ve done rope rescue courses; I’ve really worked on those technical skills and worked on my mountain sense; going out with mountain athletes and asking them what their thought process is when they’re out there managing and mitigating risk. I find myself thinking a lot more about risk and as my technical competence has gone up, interestingly enough, I can actually do what on paper may be risker things, but you can do them in a much more knowledgeable way.

Something that is really driving the world of outdoors, are technical advances in kit; equipment is becoming lighter, more focused, more specialised, and clearly designed to help athletes push further. What stand-out items or technological advances have allowed you to do more in the mountains?

“I think the biggest advances are cell phones and technology; the access to information that you have. Before you go you can get a lot of route data; find out what the weather is going to do, review avalanche bulletins, speak to other people that have been there before you; you can get this mass of information that previously you may not have been able to get yourself. You can build a knowledge base, but it doesn’t change the fact that you still need to make decisions, in the moment.

“There’s a big discussion in mountain sports about the lack of modern mentorship; you can get a lot of information nowadays but it doesn’t replace in the field experience; you need to spend time outside; thinking about what you’re doing and moving through. We have unbelievable tools at the moment; our gear is lighter than ever and because of that, why not bring an 80g jacket with you, why not have a super lightweight harness or super lightweight rope, or not pack your cell phone or take a space blanket; the gear that you have now is just so light it does give you a slightly larger margin for safety. Ultimately though, the biggest preventative tool is not to get yourself into a situation in the first place, to have to rely on those tools; your mountain sense is still the most valuable piece of equipment you have.”

Looking back to the day of your accident, is there anything that you weren’t carrying that day, that with hindsight might have materially improved the outcome? Is there anything that you would consider to be an absolutely essential, must have item?

“There’s nothing that we didn’t have. We brought the absolute bare minimum, but we had everything we needed. We had a space blanket, we had an emergency bivvy, we had down jackets. You need to think about what you would need to have if you were to get stuck out; especially as a trail runner and going for these big mountain runs, you can really get out there, a long way away.

“So, a few things I always use; I always let somebody know where I am going. If I’m going somewhere there’s no cell signal I do bring an InReach with me, especially on an all day route. I always have a jacket with me and a buff, and just enough food and water. I still like to bring the minimal amount of gear, but I do give myself a little margin of safety. Whether that means bringing one or two jackets, bringing a slightly bigger pack. At the end of the day, it really doesn’t weight that much more.”

Has your accident changed your view of solo mountain travel? Would you be less inclined to travel alone now? Have you adapted your strategy or how you manage the risk?

“I have been thinking about that quite a bit; especially when it comes to ski-touring alone in the winter and whether or not that’s a good idea. And I ask the question why would you be willing to something in a group that you’re not willing to do alone? If that makes sense?

“I quite enjoy my independence, I love my alone time, I get a lot of pleasure from that, but for some objectives it doesn’t make sense to be by yourself. Like going for a technical climb – I’m not physically capable of soloing it, you’re faster as a group in certain environments; you might have different skill set; so, there are times when having a very good partner makes a big difference.

“But in terms in solo travel, there’s a time and a place for it for sure, and I love it, and there’s an incredible power in it; it is nice to be self-reliant and think about what you’re doing; you should probably be a little more cautious, but I don’t think you should be doing anything in a group that you wouldn’t do by yourself.”

There are more and more products specifically designed for Trail Running and I’ve seen that increasing in the Arcteryx range as well. Have you been involved in the design, development and testing of these products?

“I’ve been with Arcteryx since 2009, which is before they had any running specific products, so I’ve been intimately involved with every piece of apparel that exists in the running line. I’ve prototyped everything that’s out there. When I was living in Vancouver it was amazing, because the design centre is right there and they can whip up a product in the factory at the time; we’d go test it, come back, make modifications. All of the designers that work there are incredibly active themselves; so they’re all testing the products as well.

Adam training in his backyard in British Columbia, Canada

“I wasn’t involved in the 1st generation of running shoes, because I was with Salomon at the time, but I’ve been involved with the current Norvan LD, which is a beautiful running shoe for mountain adventures. It’s a really cool, super comfortable burly shoe with very tacky rubber; it’s really sticky which for obvious reasons is very important to me!”

I’m super excited by that shoe actually, I’m going to be reviewing that in the coming weeks and months; I’ve always felt there’s been a vacuum within the Arcteryx range for a shoe that performs as well as their other products.

“It runs really well. The thing to keep in mind is that Arc’teryx’s focus is not on racing, it’s trail running and mountain running; proper mountain adventure. It’s a little bit beefier, because it has to be. The last thing you want when you’re out doing a big mountain run is for your shoe to collapse on you, or to rip or break. You do need just a little bit more shoe than you would for specific racing; the shoe is designed for going up the mountain for 12 or 14 hours, possibly 2 or 3 days in a row.”

Do you think there is much more scope for equipment development and innovation? Where do you think the greatest scope remains for innovation in outdoor products to support running in the mountains?

“Customisation; I think that’s the future, with 3D printing. Being able to have a shoe that’s moulded and designed specifically for your foot. I really don’t think were far away from that.”

I would be really interested to hear what you plans for the year ahead and beyond? Where is life and work taking you?

“I have a couple of races planned for this summer. I’m doing a race in China on the 12 May 2018. It’s a 65k race that I’m really not ready for, with 4500m of elevation gain and the whole race happens between 2500m and 4600m and it looks quite technical. I’ve been asked to go on a speaking tour with the ‘In Constant Motion’ movie Arc’teryx are releasing, which is an amazing opportunity, so I’ll be travelling around China a little bit and Japan. I’ll actually be in Chamonix this summer, at the Alpine Academy Arc’teryx are putting on, and after that I’ll be in Squamish at another Mountain Academy that Arc’teryx put on there.

“Beyond that, we’ve got this unbelievable backyard in Canada, we’ve got these really big remote mountains that don’t really get a lot of attention but they’re quite impressive ranges; Mount Logan up in the Yukon which is actually the biggest mountain by mass in the world and it’s the second highest mountain in North America so I’d love to spend some time back there. You’re remote in those areas. It would take days just to get back there. You’re self-reliant. The main goal this summer thought is to keep working on my mountain skills; to spend as much time outside with really good friends and some of my mentors; I’ve got some local projects that involve linking up peaks and a little bit more technical climbing and then running in between the peaks; that kind of stuff really interests me at the moment.”

Adam Campbell will be participating in workshops at this year’s Arc’teryx Alpine Academy in Chamonix, and in the meantime you can watch the award-winning short film ‘In Constant Motion’ HERE.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Kev Foster is a competitive trail runner and avid ski tourer, and starts training for his International Mountain Leader Award in spring ‘18.